ANALYSIS: Pacific leaders have declared a Blue Pacific “Ocean of Peace” - yet many warn the document misses a chance to ground peace in Pacific values and practice.

The Blue Pacific Ocean of Peace declaration was signed earlier this month at the 54th Pacific Islands Forum leaders meeting in Honiara, Solomon Islands.

While leaders hailed it as a milestone, critics say it overlooks the harms of militarisation and ongoing struggles for self-determination, even as it highlights the potential for women-led peacebuilding.

History repeats: no peace without justice

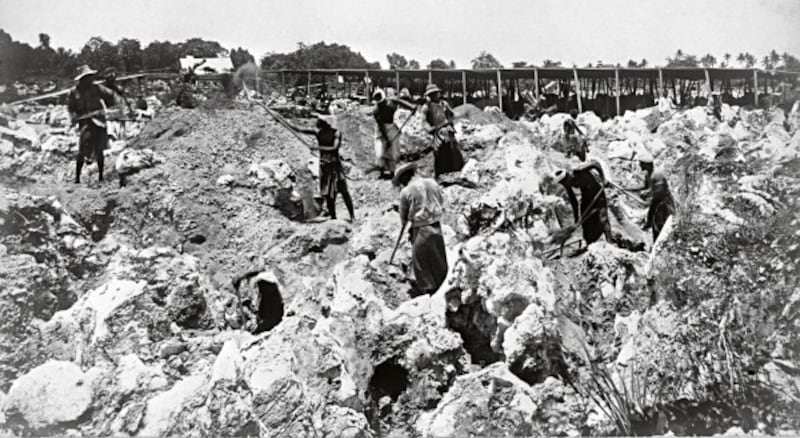

For Pacific peoples, the language of peace is not new. Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa was named the “Pacific” by Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan in 1520 after the calm waters he encountered - but behind that name came violent extraction and colonisation.

His voyage opened the ocean to European empires, whose “discoveries” ushered in missionary control, resource exploitation, nuclear testing, and large-scale dispossession.

This latest declaration, however, was advanced by Pacific leaders themselves. Solomon Islands Prime Minister Jeremiah Manele described it as a “solemn vow that our seas, air, and lands will never be drawn into the vortex of great power rivalry,” invoking the brutal Guadalcanal confrontations of World War II.

Yet many argue the document still falls short of shielding the islands from such rivalries.

“It’s like the cycle has come back around again,” said activist Hilda Halkyard-Harawira. “When I was much younger, we used to talk about peace as not just the absence of war. A lot of the elders would say without justice, there is no peace.”

She pointed to the legacy of the Nuclear-Free and Independent Pacific movement, which helped stop France’s nuclear testing in Mā’ohi Nui and prevented Japan from dumping nuclear waste in the Marianas Trench.

But she noted with concern that Japan is now releasing nuclear wastewater from the Fukushima disaster into the Pacific Ocean. While the movement successfully stopped French nuclear testing in Mā’ohi Nui, she noted that young people, such as Hinamoeura Morgant-Cross, continue to suffer from intergenerational cancers.

Dr Jenny Te Paa-Daniel (Te Rarawa), former director of the National Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies at Otago University, linked the discussion back to Aotearoa. “Moana Jackson helped us understand that Māori being able to live as Māori in our own country is essential for peace and justice,” she said.

Halkyard-Harawira added that many of the gains Māori fought for over the past 50 years are now being stripped away. “For me, an act of peace is to vote out the current government at the next election in response to policies harming Māori wellbeing.”

Security versus peace

Reverend James Bhagwan of the Pacific Conference of Churches, which contributed to the Forum discussions, questioned how seriously leaders were committing to peace when Fiji had just opened an embassy in Israel. Prime Minister Sitiveni Rabuka defended the move as neutral and in Fiji’s interests, while still expressing moral support for Palestinian aspirations.

Bhagwan recalled that the Ocean of Peace was originally promoted as the “twin” to the Boe Declaration — Boe dealing with regional security, this one with regional peace. Yet, he said, the final text feels less like a pivot to peace and more like an updated security framework folded into the 2050 Blue Pacific Strategy.

He said the declaration recognises threats but avoids naming or rejecting foreign bases, live-fire exercises or military build-ups. By failing to include demilitarisation or other concrete safeguards, Bhagwan argues, it risks normalising militarisation under the language of “peace and security.”

‘The Ocean of Peace is no Treaty of Rarotonga’

Before the tabling of the document, Pacific historian Dr Marco de Jong warned that the declaration risked being co-opted, cautioning that rather than being an Ocean of Peace, it could become an Ocean of Pacification.

De Jong welcomed references to responsible innovation and climate action and particularly celebrated the acknowledgement of the role of communities, civil society, and women’s organisations in building peace.

However, he also urged reflection on how easily the declaration could be co-opted through “integration” and forum-endorsed mechanisms, noting that some clauses facilitate peacekeeping aligned with broader geostrategic objectives.

“The failure to include ambitious language on demilitarisation and decolonisation is a missed opportunity and reflects the declaration’s contradictory purposes and divides in regionalism,” De Jong said.

At first glance, the Pacific as a Zone of Peace seems to echo the Treaty of Rarotonga and its promise of a South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone. But, looking at the final adopted document, De Jong concluded, unfortunately, the Ocean of Peace is no Treaty of Rarotonga

The missed opportunity: Indigenous Pacific ideas of peace

Bhagwan said that while the declaration is full of technical and political language,” there is no articulation of Pacific understandings of peace that are deeply embedded in Pacific cultures and Indigenous spirituality.

“Peace is a way of being; a wholeness. It is living with people and the environment in balance, co-existing with the understanding that each contributes to the flourishing and thriving of one another,” he said.

Dr Jenny Te Paa-Daniel added, “Peace or rangimārie is an inevitable state of being when all the preconditions are met that allow for human flourishing.”

Bhagwan argued the declaration could still have addressed security while being grounded in Pacific principles and values — but “we missed an important opportunity.”

“Declarations are supposed to be red lines, and there’s a difference between a red line on the ground and a line in the sand. When it’s a line in the sand, the waves of geopolitics are going to erode that line very quickly.

“The principles and values are the rocks that stand firm and are not moved. They are the reference point to move back to when needed.

“But if you draw a line in the sand, once that washes away, what do you do? You’ve got to keep drawing lines — and for me, that is the challenge. We can find points to anchor, but that’s us searching rather than it being there for all to see. Without foundational principles, you can make this declaration fit anything you want.”

High rates of violence against women

“We cannot talk about peace and security without talking about the rate of violence in the Pacific,” emphasised Viva Tatawaqa, executive director of the Fiji-based Pacific feminist collective DIVA for Equality.

DIVA develops programmes, tools, and supports organisations addressing issues from food sovereignty and climate justice to temporary housing for unhoused single mothers, children, disabled people, and survivors of domestic violence.

Tatawaqa and DIVA colleagues Noelene Nabulivou and Vika Kalokalo, as part of the Pacific Women’s Media Network, briefed the Pacific Islands Forum throughout the Ocean of Peace declaration’s development.

New Zealand already has the highest rates of domestic violence and violence against women in the OECD, and UNICEF has reported it among the highest for child abuse in the developed world. Rates across the Pacific are even higher, with two in three Pacific women experiencing physical and/or sexual violence in their lifetimes.

“The domestic sphere is a microcosm of the global sphere,” said Dr Jenny Te Paa-Daniel. “It’s patriarchal dominance that’s led us into this mess and the very dangerous political-economic climate moment.”

Waimarama Hawke of Te Kāhu Pōkere, a rangatahi delegate to the UN Climate Summit in November, said: “The oppression of women and the oppression of the planet are one and the same. Both are rooted in colonialism and misogyny. If we want to see a healthier planet, waterways and environment, we need to start with the health of Indigenous women.”

Women as builders of peace

At the same time as being victims of violence, many argue it is women who are the builders of peace.

Sharon Bhagwan-Rolls, coordinator of political engagement for the Pacific Women Mediators Network, was not surprised by the absence of the word “demilitarisation”, given the need for consensus among leaders. She welcomed the linkages to the Universal Declaration on Human Rights as an accountability framework and the wording of “women and girls in all their diversities”.

In her briefing to the Pacific Islands Forum last year, she reminded leaders that the call for a zone of peace came from Pacific Island women at the 1994 meeting, which adopted the Pacific Platform for Action, and that it was civil society who ensured the Blue Pacific Strategy had a peace and security pillar.

“Peace builders are first and foremost women in the homes in our region; it is women holding communities together in conflict zones and ensuring there are non-violent approaches to what is happening,” Bhagwan-Rolls said.

“Unfortunately, we have some of the highest rates of violence in our communities, and we also have the lowest representation in terms of decision-making.”

Bhagwan-Rolls also noted the role of faith leaders in peacebuilding, such as Pastor Billy Wewetea from Kanaky (New Caledonia) where local church leaders helped community healing, cultural expression and calls for peace throughout the riots last year.

Hilda Halkyard-Harawira said in Aotearoa, wāhine come as mothers and grandmothers, and that played a significant role in maintaining peace in resistance.

“Women don’t like people wasting time fighting, and we don’t want our sons to die in useless battles that aren’t of our making,” Halkyard-Harawira said.

Militarisation, masculinity and trauma

James Bhagwan said the declaration should also have addressed internal conflicts and trauma-fuelled violence in communities, families and homes — especially its impact on women and children.

Militarisation, he argued, reinforces toxic masculine norms of aggression, dominance and suppression of vulnerability. He said men are taught that aggression and dominance are exemplified as being manly, and it leaves no space for nurturing.

“I live in Suva, in a militarised society where even the security guard feels that they are some sort of soldier. That demeanour, the culture of toxic masculinity, is a result of militarisation,” he explained.

“[Fiji] send peacekeepers around the world; we serve in conflict zones, and people come back traumatised. I would say, when you wear your armour for long enough, you forget that you have it on, and forget to take it off… and they bring that armour into the house, and those are hard edges versus the soft edges of peace and love. “

By contrast, Jenny Te Paa-Daniel invoked Moana Jackson as an example of peace and ngākau māhaki while still confronting injustice.

“One requires a transformation to live gently… the encouragement of all to live gently with one another, with creation, with the environment,” Bhagwan said.

Sharon Bhagwan-Rolls drew a line between geopolitics and militarisation. While geopolitics will always exist, she said, “Militarisation threatens all our peace and human security because if you look at the money invested into military hardware instead of development projects such as agriculture, education, climate justice, military funding isn’t actually investing in conflict prevention.”

She went further to say, “Military spending is a grave concern of women’s rights and feminist peace builders as the militarised approach ignores women’s lived insecurities — poverty, healthcare, climate vulnerability.”

She also noted that conflict zones have higher rates of sexual violence and abuse against women.

Peace and development

Speakers emphasised that achieving peace requires addressing the root drivers of conflict and instability. Sharon Bhagwan-Rolls said the link between peace and development is especially important for Small Island Developing States, where issues like infrastructure gaps, poverty, and climate impacts directly contribute to instability.

Hilda Halkyard-Harawira added that peace also means ensuring policies and practices don’t rob people of a good life. Last year, Pastor Billy Wewetea highlighted multiple factors behind the riots in Kanaky, including ignored political frustrations, social inequities in poverty, education, and housing, and a proposed electoral reform seen by youth as undermining decolonisation.

Vika Kalokalo stressed the importance of civil society in peacebuilding, restorative justice, and conflict transformation, noting the need for further resourcing. Sharon Bhagwan-Rolls sees the Ocean of Peace declaration as an opportunity to strengthen regional peace-building architecture and localise peace efforts.