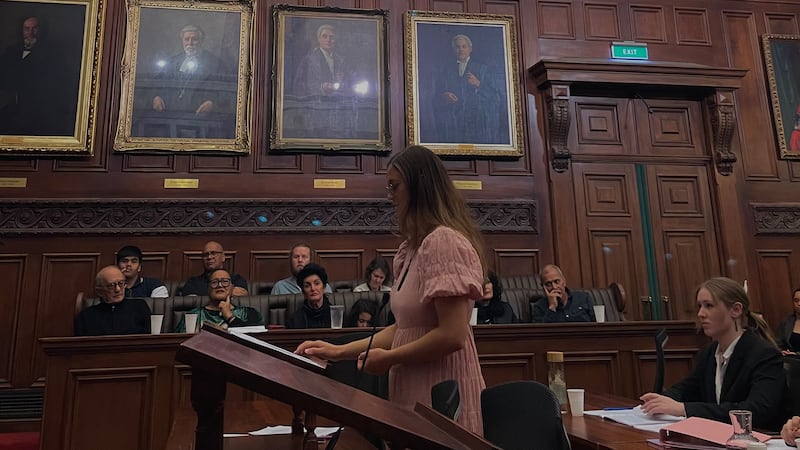

Aria Ngarimu (23)

Aspiring Community-Based Advocate

Aria (Ngāti Porou, Ngāti Kahungunu ki Wairoa, Rongomaiwahine, Te Whānau-ā-Apanui) is a proud wahine Māori and emerging researcher, currently completing a conjoint Law and Science degree at Te Herenga Waka-Victoria University of Wellington. As Co-Tumuaki of Ngāi Tauira, she advocates for tauira Māori and Te Tiriti-based collaboration.

Her research explores climate change, Indigenous food sovereignty, and mental health, reflecting her commitment to Indigenous self-determination and systemic change. Through her leadership and advocacy, Aria hopes to shape a more just and equitable future for Māori and other marginalised communities.

Q. In practical terms, what does Te Tiriti-based collaboration mean to you in your mahi, and where do you see it being effectively implemented or falling short?

To me, Te Tiriti-based collaboration means understanding that we all have roles to play in upholding Te Tiriti, both tangata whenua and tangata Tiriti. I feel like a lot of the emphasis has been on the Crown and tangata Tiriti upholding their end of things, which is completely justified and understandable, but I think it’s also important to remember that as tangata whenua, we also have obligations not just to tangata Tiriti, but to ourselves.

If we want this relationship to be as beneficial as possible to both parties, we need to build strong iwi, hapū, and whānau structures that exist independently from the Crown and Pākehā systems. There are opportunities for this everywhere, through reclaiming our language, practising our environmental and cultural responsibilities, and healing intergenerational trauma.

Q. Your research touches on food sovereignty and mental health. How do you see these issues linking to the wellbeing of rangatahi?

Climate change and mental health are two of the biggest issues that young people are concerned about today. My research looks at food systems as one area where these issues overlap, asking the question: Where does our food come from? If we are relying on industrial food production systems that contribute to climate change, damage the land, and displace our people, then that will affect our mental health and our sense of future security.

Furthermore, practising food sovereignty creates opportunities for positive outcomes. It helps people reconnect with the environment, strengthens relationships across generations through the sharing of knowledge related to food practices, and builds confidence in people to provide for themselves and their communities.

Q. What are the changes you most want to see in Aotearoa for Māori in the next 10 years?

I want to see Māori reclaiming more autonomy and building self-sufficiency across all areas of life, including our language, economies, food systems, housing, education, and the justice system. I don’t think these changes will be realised overnight, or even within the next 10 years, but I think they are the kinds of goals we should be dreaming about and working towards now.

No one can fix everything on their own, but if we each do our part, across generations and over time, then we can make the world a better place.

— Aria Ngarimu

Ivy Lyden-Hancy (19)

Storyteller, Poet & Indigenous Advocate

Ivy (Te Rarawa, Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Wairere, Samoa-Falefā, Tonga-Vava’u) is a wahine Māori creative and advocate from South Auckland, dedicated to uplifting Māori and Pasifika communities through her mahi and spoken word poetry.

As a cultural practitioner at Te Whare Hinātore, she supports wāhine experiencing housing insecurity, alongside community work with Talavou Village and Village Collective.

The first in her whānau to attend university, Ivy is studying History and Māori Media at AUT. Her storytelling and leadership reflect her commitment to Indigenous equity, with aspirations to become a lecturer and filmmaker.

Q. You were the first in your whānau to attend university. What helped you get there, and what advice would you give to others on a similar path?

I am the first in my whānau to attend university, but I am also the first in my family to finish high school, which was an accomplishment in itself, let alone receiving DUX. My kaiako at Papakura High School are really what pushed me into going to university.

I never really was interested in being an academic until I was introduced to poetry. Zech Soakai was my reason for going into academia, he started a poetry collective called the 298 Urban Orators, where a group of us worked on our craft and built bonds that have lasted years.

I am now published in multiple anthologies, zines, magazines, and poetry collections nationwide, and am grateful I had it as a lifeline to university. Advice I would give to those on the same path as me is: take every opportunity you get! Your mana is held in the way you reciprocate your teachings and mātauranga.

Q. What are some challenges you’ve faced as a young wahine navigating institutions or systems, and how have you overcome them?

When I had my first internship, I was told by a staff member, “I don’t know why Māori get special scholarships,” and they went on a tangent after assuming I had got that internship through a “special Māori scholarship”. In actuality, I was on an academic scholarship that had nothing to do with my identity as Māori. That moment stood out to me as it set the tone for how I, and Māori alike, can be perceived both in the corporate and academic world.

Māori need to receive equitable chances at success, as we currently live in a society where Indigenous resurgence is weaponised. Equitable resources for all sectors must be upheld if tauiwi and Māori are to live as partners, specifically in the education system where Māori are misrepresented and underrepresented. There are numerous platforms and resources created by Māori, for Māori, yet there is little support given by the Crown services who we have a treaty and partnership with.

Q. What are the changes you most want to see in Aotearoa for Māori in the next 10 years?

For there to be a clear recognition of Indigenous resurgence and an improvement of land restoration and protection. Ko au te taiao. Māori are the land, and the land is people. There is a clear lack of recognition of land ties, where land is only seen as resourceful when it is profitable, but te taiao is beautiful merely for just existing. Māori recognise this, and for Aotearoa to have equitable outcomes for Māori in the next 10 years, there needs to be an understanding that ‘land back’ does not necessarily mean to just give land back, rather it’s about honouring it in its entirety.

Honouring the land comes with acknowledging climate change will and is directly affecting Aotearoa. I hope in 10 years, there is a conscious effort by the Crown and government in land restoration and protection; this will further provide equitable outcomes for Māori in Aotearoa and will honour Article 2 of Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

Lauryn Maxwell (22)

Te Ao Māori & Health Equity Champion

Lauryn (Ngāti Pūkenga ki Waiau, Ngāti Maru, Ngāti Kiorekino) is a proud wahine Māori from Tauranga Moana, passionate about uplifting Indigenous voices and advancing health equity. With a background in psychology and Māori development, she’s pursuing postgraduate studies in public and Māori health.

As a kaupapa Māori advisor at 2degrees, Lauryn brings cultural advocacy into the corporate space. Her journey includes public health work in India, which helped ground her in reclaiming her reo, whakapapa, and tikanga, and she’s committed to creating accessible, culturally grounded healthcare for all.

Q. What does truly equitable healthcare look like to you, and how close are we to achieving that in Aotearoa?

Truly equitable healthcare means everyone can access care that fits their needs, culture, and identity, not just the same care for all, but care that recognises our different realities and strengths. For Māori, it means services designed by Māori, for Māori, grounded in Te Tiriti o Waitangi and mātauranga Māori.

We’re still a long way from that vision. Real equity will take systemic change and Māori leadership at every level of the health system. It also means listening to our communities, valuing lived experience, and making sure whānau voices guide decisions.

Q. How do you navigate being a young Māori woman in public health and corporate environments where systemic barriers still exist?

It’s important to remember why you are there and what you’re passionate about. For me, it is to bring a Māori perspective and keep our communities front of mind. I see it as part of the kaupapa: being willing to question, challenge, and disrupt systems to make them equitable for all.

It is important to acknowledge that my mahi isn’t done alone. I lean on mentors, peers, and whānau for support. It’s about finding balance, knowing when to speak, when to listen, and making sure I’m not the only Māori voice in the room. Making space is important, not just for myself, but for other Māori voices, so that over time, the room itself starts to change.

Q.What are some challenges you’ve faced as a young wahine navigating institutions or systems, and how have you overcome them?

One challenge has been navigating spaces that weren’t designed for Māori and women. Our voices can often be sidelined or tokenised. It can be hard to share opinions and ideas when you feel your perspective isn’t the norm. What’s helped is remembering I’m speaking as an individual, but for a community and those who come after me. Building relationships with people who genuinely value what I bring has also made a difference; it turns the mahi from pushing against something into working alongside others for change.

Improving outcomes means honouring Te Tiriti o Waitangi, empowering Māori to lead, and designing systems that work for us. A big part of that is empowering rangatahi.

— Lauryn Maxwell

Mairātea Mohi (25)

Māori Publisher of People, Place, and Story

Mairātea (Ngāti Rangiwewehi, Te Arawa whānui, Te Whānau-ā-Apanui) is a publisher and writer dedicated to bridging cultures through storytelling. Raised among iwi elders at Lake Rotorua, she learned to carry whakapapa and identity through words.

As Craccum’s (Auckland University’s student magazine) first Te Ao Māori editor, she launched Māori and Pasifika-led issues and helped embed Indigenous voices in leadership. She now works as te reo Māori Publishing Associate at Waipapa Taumata Rau, uplifting Indigenous, Pacific, and migrant stories that centre identity and decolonisation.

Q. How do you think Māori publishers can change ideas about what counts as important or valuable writing in a system still shaped by colonial thinking?

If you look at the traditional role of publishers, they’ve long been positioned as gatekeepers of culture, taste, and knowledge dissemination.

In some ways, Te Ao Māori carries its own forms of guardianship, with knowledge often held and shared through specific modes of tikanga and by particular tohunga. With that history in mind, Māori publishers have an opportunity, and a responsibility, to create space for forms and ideas that fall outside conventional literary moulds. That means backing community narratives, championing ‘small’ stories, and pushing for experimental work that may not align with literary norms.

It also means redefining what we measure as success. Moving beyond commercial models or critical acclaim and valuing writing for its mana, and its endurance within the community. For me, that looks like developing deep relationships with our Ringa Tuhi and hoping they allow us, the publisher, to join them on this never-ending journey of knowledge acquisition.

Q. How do you navigate the balance between cultural integrity and mainstream publishing expectations when uplifting Indigenous and migrant stories?

Ki te anga whakamua, me tū māia ki te pae tōtika o ngā uara, ā, ko te manaakitanga me te whanaungatanga tērā. Ki te ngaro ēnei, ka paheke te kaupapa.

Me maumahara tonu, ko te tangata te pūtake o te ao. Ko te tangata, ko te kōrero hoki. Nā reira, ko te haepapa o te hunga waituhi pukapuka ko te hiki i ngā hapori katoa ki te tūāpapa, kia rangona, kia kitea.

Ko ngā kōrero o te ao Māori, te ao Moana, ngā kōrero a ngā iwi manene, a ngā tāngata whaikaha - koirā ngā kupu e whakaatu ana i te kanorau o Aotearoa i ēnei rā. Ngā reo e tuituia ana i te whenua.

Ehara tēnei i te kaupapa whai pūtea, whai tohu noa iho. Ki te kore e ū ki te manaakitanga me te whanaungatanga, ka hē, ka riro kē te kaupapa hei mea hokohoko, hei tango rawa rānei.

Ehara i te mea he āki i tētahi kōrero anake, engari me hiki tahi ake te tangata, te hapori me te kaupapa i te haere ngātahi. Ko te angitu tūturu, he mahi ngātahi.

I te mutunga iho, ko te hiahia o te tangata kia rangona, kia kitea. Koirā te pito mata o te mahi nei.

Q. What are the changes you most want to see in Aotearoa for Māori in the next 10 years?

Ko ngā panoni e tino hiahia ana au mō te Māori ko te tino rangatiratanga, i roto i ngā ao hautūtanga, te whakahaere, me te whakatau kaupapa. Kāore kia noho hei tētahi tohu, he tauira rānei, engari kia noho hei mana tūturu e whakakotahi ana i ngā kaupapa, ngā tikanga me te wairua Māori.

What I want most for Māori in Aotearoa over the next 10 years is true power-sharing in leadership, governance, and decision-making. Not token representation, but real authority that reflects who we are and what we stand for.

Me whakarewa mātou i ō mātou ake kōrero. E kīia nei, ngā mea pai, ngā mea kino, ngā mea uaua. Kia whakamanahia te reo, te āhua, me te mana o te tangata Māori i roto i ngā āhuatanga katoa o te ao hurihuri nei.

I want to see our stories told fully, ngā mea pai, ngā mea kino, the good, the hard truths, the whole picture. Our narratives should be front and centre, unapologetically Māori in all their complexity.

It means creating spaces where Māori voices shape policy, education, media, and culture, not as an afterthought, but as a foundation.

I te mutunga iho, ko taku moemoeā kia tū rangatira ai ngā Māori i raro i te māia, kia taea e tō mātou rangatahi te tiki i tō rātou tūranga, ā, kia ū hoki te wairua o te Tiriti o Waitangi i roto i ngā mahi, ehara i ngā kupu noa iho.

Ultimately, I want to see a future where Māori rangatira lead confidently, where our rangatahi feel empowered to claim their place, and where the spirit of partnership laid out in Te Tiriti o Waitangi is honoured in practice, not just words.

That is the change that will sustain us for generations to come.

While the act of publishing may not be ours, storytelling is. My hope is that through my mahi, more of us will feel like we belong in this space, because we have every right to be here.

— Mairātea Mohi

Ellathea Tia Fleming (22)

Māmā, Indigenous & Community Changemaker

Tia (Ngāti Apa, Ngāti Kahungunu ki Wairarapa; various Samoan villages) is a 22-year-old māmā, student, and community leader studying at the University of Otago.

Raising her tama has fuelled her passion for creating positive change and building supportive communities. Involved in initiatives like The Hive and Talavou Village.

The young māmā has held leadership roles in Māori and Pasifika student associations and Kōhanga Reo. Through her mahi, she uplifts others and embodies the strength and resilience of young wāhine Māori and Pasifika.

Q. How has becoming a māmā shaped your leadership journey and commitment to your community?

I don’t think it’s changed much other than adding a new perspective to the way I look at things. I think I would have continued to do some of the mahi I’ve been involved in with or without a pēpi, but being a māmā, I definitely see that it has deepened my reasons and drive to do things.

I think about the sustainability of te taiao and what are things that we do today that affect our tamariki? I think about barriers that I face, or challenges that I face, there must be others facing similar things,, if not harder, and I think about what are ways that I can contribute to change, while also ensuring that I am looking after my own hauora.

Having a pēpi definitely taught me to make sure that I’m not pouring from an empty cup, and I need to make sure I’m filling my cup to then give to others and especially those that need me the most. Tamariki are the coolest; they run on their own maramataka, and when you act as their pou (support pole), they are tau (content), they feel it. When you’re not, and there’s that riri (anger), oh they feel it :)

Q. What do you think are the most important values to teach our tamariki and rangatahi growing up today?

To whakamana (empower) themselves and each other. Life gets hard and harsh, but holding onto their beliefs and values will be something that gets them through those hard times, but also when things get easy or stagnant as well. Values such as whānau, aroha, and tika will be the things that help them shape their own perspectives on life and what directions they want to go.

Also, change as well, where we’re allowed to have a change of beliefs and a change of perspective. Values may be rooted in them, but if they don’t resonate, kei te pai, it’s okay to figure things out.

Q. What are the changes you most want to see in Aotearoa for Māori in the next 10 years?

To not have to be fighting the same whawhai. I don’t want to have to see my son protesting against bills that are trying to erase our governance.

Access is another huge thing: access to facilities, access to support, education, voting, our reo. But it goes both ways I want to see accessibility to these things, but I also want to see our rangatahi being involved and feeling safe and empowered to be able to involve themselves.

Q.What are some challenges you’ve faced as a young wahine navigating institutions or systems, and how have you overcome them?

Sometimes, being the only Māori or Pasifika person in the room, your voice is expected to be a voice for all of that community. There are times when I’ve had to step back, have a think, and say: “No, this is my opinion, and I’ll speak for my experience. But don’t rely on us to speak on behalf of communities that you need to reach out to and have relationships with.”

Te Ahipourewa Forbes (21)

Rangatahi Advocate & Media Visionary

Te Ahipourewa (Ngāti Pāoa, Ngāti Maniapoto, Ngāti Naho) is a Māori multimedia journalist at Re: News, dedicated to amplifying Māori voices and reshaping Aotearoa’s media landscape. Covering cultural, political, and social issues, her storytelling celebrates Indigenous identity and challenges mainstream narratives.

Grounded in whakapapa and tikanga, she views journalism as modern Māori storytelling-restoring dignity to her people’s voices and inspiring rangatahi through stories rooted in mana motuhake and whanaungatanga.

Credits:

Journalist/Producer: Natasha Hill

Graphics Designer: Joy Casilang