Fourteen years ago, Dr Lance O’Sullivan was working in the Kaitaia Emergency Department, trying in vain to save the life of a two-year-old murder victim, the same age as his own daughter at the time.

“I had a lot of PTSD for that,” he admits. “I’m here for that, and to see that happening in our communities so close to home is heartbreaking, to be honest.

O’Sullivan walked alongside adults and children in Kaikohe, holding balloons and blowing bubbles at a rally earlier this month, where hundreds gathered in solidarity to share their grief and commemorate the life of Catalya Remana Tangimetua-Pepene, who was allegedly murdered on May 21.

Last week, 45-year-old Drummond Augustine Leaf pleaded not guilty to the charge of murdering the three-year-old girl.

“What are we missing that are keeping our children safe?” asks O’Sullivan. “It’s a massive concern that over a decade later, we’re still seeing this.”

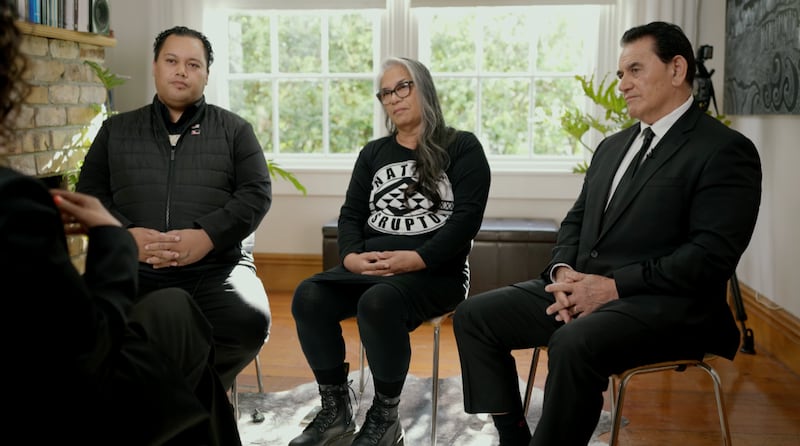

NZ First Deputy-leader, Shane Jones (Ngāpuhi, Te Rarawa), pointed to ‘the spread of the drug culture’ and admitted how big the ‘challenge (is) to create solutions with the community.’

“Cops can’t arrest society out of these dramas. I would say to Kaikohe that whānau leaders need to intervene rapidly when they see dysfunctionality. It’s a wake-up call for those people managing those complexes if you’re not going to retain a level of authority and maintain standards,” Jones told Te Ao with Moana.

‘Fuel public misunderstanding’

When asked whether his comment was fair, CEO of Te Hauora o Ngāpuhi, Tia Ashby, said it was “absolutely not.”

“These claims are not only inaccurate, they fuel public misunderstanding. We were not silent, we responded to the trauma within our community while respecting the police investigation.”

The toddler, who lost her life, was not a tenant of the housing complex run by Ashby, although the man on trial for her murder was.

The CEO explained how housing providers like hers receive a list of people from the social housing register who are allocated a priority rating.

“Based on that, we have to place them into our units.

“95 percent of those tenants are fantastic. Rents are paid on time. Some of them grow beautiful gardens. They look after one another. They’re living in safe, warm, secure homes,” said Te Hauora o Ngāpuhi CEO.

However, it’s the 5% that create persistent challenges.

Ashby attributes it to ‘hidden vital information’ that resides with other government agencies, such as the Police, Justice, and Child protection services.

“There are mental health and addiction issues that we don’t have visibility over,” she said, adding that these are not unique to Kaikohe, that many providers across the country report similar concerns, which reflect ‘deeper, systemic failures that stem from poverty and intergenerational trauma.’"

Jones agrees, stating, “I’m sure that this mokopuna suffered at the hands of someone who has themselves been unable to deal with addiction and other social problems, so this is a difficult area. We know that all pockets of communities are challenged by drug-related dysfunctionalism.”

The child’s death sent Kaikohe into mourning at a time when whānau are also facing a well-publicised methamphetamine crisis in the region. Northland has the highest consumption of methamphetamine in Aotearoa, with nearly 2000 milligrams per day consumed per 1000 people.

Ōpōtiki style raids

Mane Tahere, chair of Te Rūnanga ā-iwi o Ngāpuhi, received push-back from the community by suggesting that Ōpōtiki-style police raids weren’t off the table during his recent meeting with Police Minister Mark Mitchell.

“We know that we are under-resourced in our region.

“I did a call around the greater baseline numbers. Whānau think we don’t need more police in Te Tai Tokerau. No, we need more baseline police. There’s not even enough of that.

“Prior to those surges and those [Ōpōtiki] raids there was a higher [meth] wastewater count after, immediately after that dropped off by half. That’s what I want for Kaikohe,” he explained to Te Ao with Moana.

The NZ First MP supports the need for “a sharp electrical jolt”, while former Police Commissioner Wally Haumaha described the complexities involved.

“It’s not just a police issue, it’s not just a government issue. It’s not just those government agencies. However, if they’re sitting in those positions and they’ve got all the information to be able to drive the support services into iwi entities, then that’s what we should be doing. It doesn’t abrogate one or the other of their responsibility to step up,” said Haumaha.

Ashby stated that the reality is that while many non-governmental organisations, housing providers, and high-needs communities face complex risks, they have limited power to act. She’s advocating for shared responsibility and proactive “inter-agency intelligence sharing, collaboration, response and accountability across all front line providers,” explaining how powerless organisations like hers are when issues come to a head.

“We cannot evict. So that’s the role of the Tenancy Tribunal. We will go and approach the tenant to say, you know, a breach has occurred. Can we offer you any support? If it’s addiction issues, the individual has to want support and help. You can’t force someone to enter into rehab or enter into support services.

“Another challenge is referring [a tenant] to specialist services that don’t exist.

“Another challenge that is significant for us is that because there’s no emergency housing and there’s a limited housing supply across all of Te Tai Tokerau, even if you do evict, eight times out of 10, they’ll re-enter our housing [complex] as an emergency housing client. But most of the time, it’s not just the tenants, it’s their visitors. And when you’ve got loitering and unruly guests coming all hours of the night, policing that is quite a challenge.”

Ashby is calling for drug testing where safety concerns exist, funding for security, and multi-agency safety plans between agencies before housing at-risk whānau. She also advocates for anonymous child harm and family violence reporting channels, independent of government agencies.

It’s an idea that the chair of Te Rūnanga ā-Iwi o Ngāpuhi is exploring.

Self-professed “creative native disruptor” Raewyn Nordstrom, who retired after thirty years working with CYPS and Oranga Tamariki, thinks it takes a village to make that change happen.

“I’ve always believed that we need to be brave enough to stand there and say to someone, ‘I don’t like what you’re doing to that baby. Gimme that baby here and I’ll look after her, and then when you sort yourself out, you [can] come get your baby back.’

“We all have those aunties and uncles that will tell you off, hug you when you’re sad, give you a telling off when you’re bad, and we need those aunties to step up in all our communities and be the village, because a lot of our people that are out there don’t have the village around them to support them.”

With over forty years in the police, Haumaha is adamant about one way to break the cycle.

“I think that [an] alternative justice program around getting people in front of our own people who can provide the services, can provide follow-up, is a safety mechanism. It has all the key elements of providing aroha, tautoko, manaakitanga to not only the offender, but to the offender’s family and also the victims.

“Otherwise, we’ll be sitting here in another five years saying, ‘What are the alternative pathways to keep our people out of prison if they commit crime?’

“Are we the architects of interventions that are going to prevent this long term? Or are we simply the interior decorators that are gonna step up when the going gets tough and suddenly we all come out and say, ‘oh my God, how did that happen?’”

Watch full episodes of Te Ao with Moana on Māori+ or Whakaata Māori every Monday at 8 pm.