NEW YORK — At the United Nations Headquarters, a Papuan elder and a Papuan youth spoke passionately about the intergenerational struggle for self-determination in West Papua.

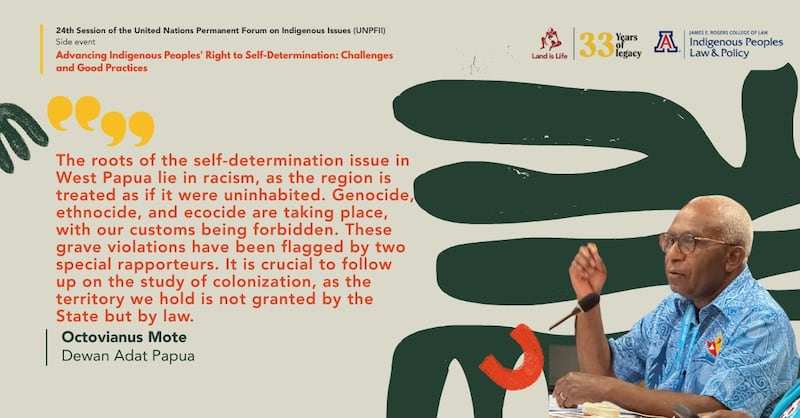

Te Ao Māori News interviewed Octovianus Mote and Defe Wabiser at the very site where, sixty-three years ago, the New York Agreement was signed, granting Indonesia administrative control over the region.

“We strongly believe that we’re not going extinct,” Wabiser said.

“West Papua is not an empty land, there are generations through generations within the forests... with our own history, our own spiritual connection with the land because we are living integrated with the lands.”

Elder Octo Mote remembers the day Indonesia invaded his village in 1968; he was fishing after Sunday mass when he saw the troops land.

“When I was in middle school... you would see the military personnel put dead bodies in the rice bag and come out of the forest like they were hunting deer.”

In the 1970s and 80s, people from other provinces told him how their family members were killed by the military.

During his university years, Papuan leaders wound up dead and were believed to be assassinated by the Indonesian forces, such as Papuan cultural revival leader, anthropologist, and musician Arnold Ap.

Mote, a former journalist, was briefly appointed as a West Papuan expert after Suharto’s fall, but fled to the U.S. in 1999 for his safety.

He recalls how, in his youth, access to historical documents was nearly impossible. Today, younger generations can learn their history and connect more easily. He admires the ongoing creativity and resilience of his people across generations.

“Now Defe’s generation, they see their friends slaughtered, beat up in front of them in demonstrations, and that act is heroism that they continue.”

Defe Wabiser, a young member of the Yali tribe, was born and raised in Jayapura and now works in Jakarta for a civil society organisation that advocates for Indigenous rights and environmental protection in West Papua.

She often reads about communities displaced by development projects.

Wabiser says her parents laid the foundation for her activism, and with today’s technology, it’s easier than ever to connect with people in Papua, the diaspora, and other Indigenous youth around the world.

She always thinks of the question of why she took up the cause, and what is the role of her generation in the West Papuan struggle.

“I work for my people as a human rights defender,” she said, “I realise that I became an activist as a coping mechanism.”

As a child, Wabiser said, witnessing human rights violations was part of daily life—military patrols, massacres, and corpses found near plantations.

“It’s something common that we hear on the news, an uncle has been shot,” she said.

Such incidents represent serious human rights violations and breaches of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

While UNDRIP affirms Indigenous peoples’ rights to their lands, territories, and resources, Indonesia, though a signatory, does not fully recognize the concept of Indigenous identity.

He tohe mō te mana motuhake

Me te aha, kei te tohe tonutia e ngā iwi o Papua mō tō rātou mana motuhake.

Ko tā te atikara tuangahuru o UNDRIP, me kaua ngā kāwanatanga o te ao e kāhaki i te iwi taketake i ō rātou whenua ki te kore rātou e whakaae, ā, me whai wāhi hoki ngā iwi taketake ki te wānanga i ngā kaupapa here e pākia ai rātou.

“When you’re not recognised as a person, there is no self-determination,” te kī a Octo Mote.

Hei tā Wabiser, he waimārie nōna ki ngā wheakoranga nō tā wāhi, me tana ako hoki me pēhea te whawhai mō ngā motika iwi taketake.

“We have the right to live, we have human rights.”

They set their recommendations to the UN:

- Honour the Responsibility to Protect (R2P), which states that if a state fails to protect its people, it is the responsibility of the other states to take collective action. R2P was endorsed by the UN General Assembly in 2005 to address concerns to prevent genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing, and crimes against humanity.

- Rather than treating human rights violations and ecocide as isolated cases, Mote urged the UN Secretary-General to mandate the High Commissioner to issue a comprehensive report.

- Follow up on Valmaine Toki’s 2013 study on the Decolonisation of the Pacific region.

- Returning West Papua to the UN’s decolonisation committee’s list - known as C24, which focuses on territories identified as “non-self-governing”.