This article was first published by RNZ.

Northland teenager Chelsea Reti marched with the Hīkoi mō Te Tiriti from the beginning.

Each day she promised her mum that it would be her last and she would return to Pawarenga. Eventually, it became clear that 15-year-old Chelsea would go all the way to Wellington. That’s when her mum decided it was the right time to send down a red beret.

“When we choose to put something on our head where we know it is going to be seen there is a significance behind it and there was significance behind why I wore a red beret,” she said.

Chelsea (Te Rarawa, Ngātiwai, Te Aupōuri and Ngāti Kahu) wore it on the hīkoi’s final day when about 45,000 protesters marched to Parliament against the contentious Treaty Principles Bill.

She wasn’t the only one.

Countless other mostly young wāhine donned a red beret for the march. It’s a pōtae (hat) steeped in history and symbolism for the Māori rights movement and other freedom movements overseas stretching back decades.

Chelsea says her mum remembered berets worn by Māori activists in the past. She also took inspiration from 22-year-old Te Pāti Māori MP Hana-Rāwhiti Maipi-Clarke, who often wears berets on significant occasions. Maipi-Clarke’s great-aunt Hana Te Hemara wore a beret when she brought a te reo Māori language petition to Parliament in 1972.

Dr Bobby Luke Campbell, a senior fashion lecturer at Auckland University of Technology, says berets were first associated with freedom during the French Revolution at the end of the 17th century. The hat was adopted and modernised by the Black Panthers, a civil rights group in America founded in the 1970s.

“They would use that as a kind of iconography,” Campbell said.

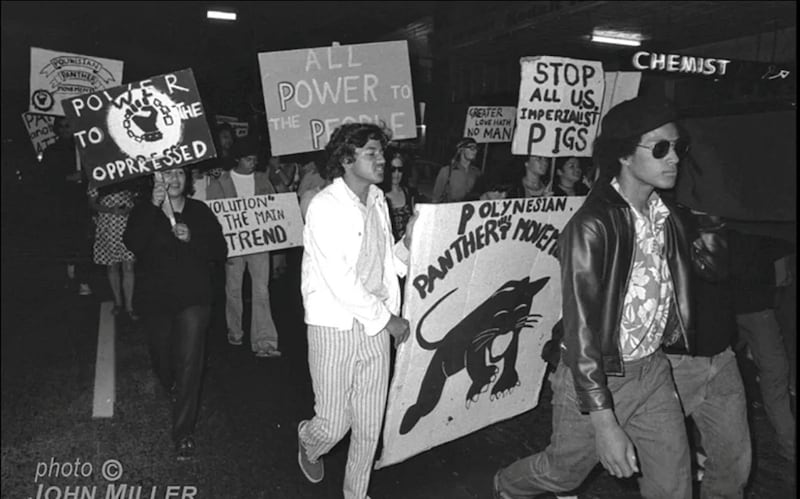

Campbell said the Polynesian Panthers popularised the beret as a freedom symbol in New Zealand in the mid-1970s, spurred by protests against the Dawn Raids. While hats are a Western symbol, they have been widely adopted and reimagined as a symbol for Māori.

On Tuesday, he saw numerous variations of the beret at the hīkoi in Wellington, including slanted berets and beret-style caps.

“The look has been re-adopted and recontextualised to support the kind of movement that we have going on now.”

Te Koha O Te Moana Shortland, 17, also wore a red beret during the hīkoi. Part of her inspiration came from the 28th Māori Battalion that fought during World War II wearing berets. The bright red of Shortland’s beret mirrored that of the tino rangatiratanga flag.

“For Māori, red is a highly important colour as it usually represents blood or bloodline, loss, history, etc,” Shortland wrote to RNZ over Instagram.

Many Māori activists have adopted different hat styles, Shortland noted, just as many kuia and kaumātua wear a range of striking pōtae at marae events. It’s hard to think of Dame Whina Cooper without her headscarf, for example, or Tame Iti and his bowler hat. Te Pāti Māori co-leader Rawiri Waititi favours a large cowboy hat, even in Parliament.

Hats are particularly important given that the head is considered the most sacred part of the body in Māoridom, she adds.

“Head adornments have long been worn by Māori as a sign of honour, power, and pride.”

Fashion designer Adrienne Whitewood’s medium-brimmed, wool hats with a plastic tiki and tāniko weave trim are so popular that she “gets them in by the thousands”.

Her Rotorua and Wellington stores were busy when the hīkoi came through, and she says there’s a practical reason to why hats are so popular with Māori.

“A lot of times when you are at the marae you are outdoors a lot and sitting outside with no shelter.”

- RNZ