Today’s High Court decision for the Crown to return the whenua owed to the beneficiaries of the Nelson Tenths Reserves marks a possible end to what is Aotearoa’s longest-lasting land case.

Te Here-ā-Nuku | Making the Tenths Whole project lead Kerensa Johnson said she expected the Crown to accept the decision and return the land without delay.

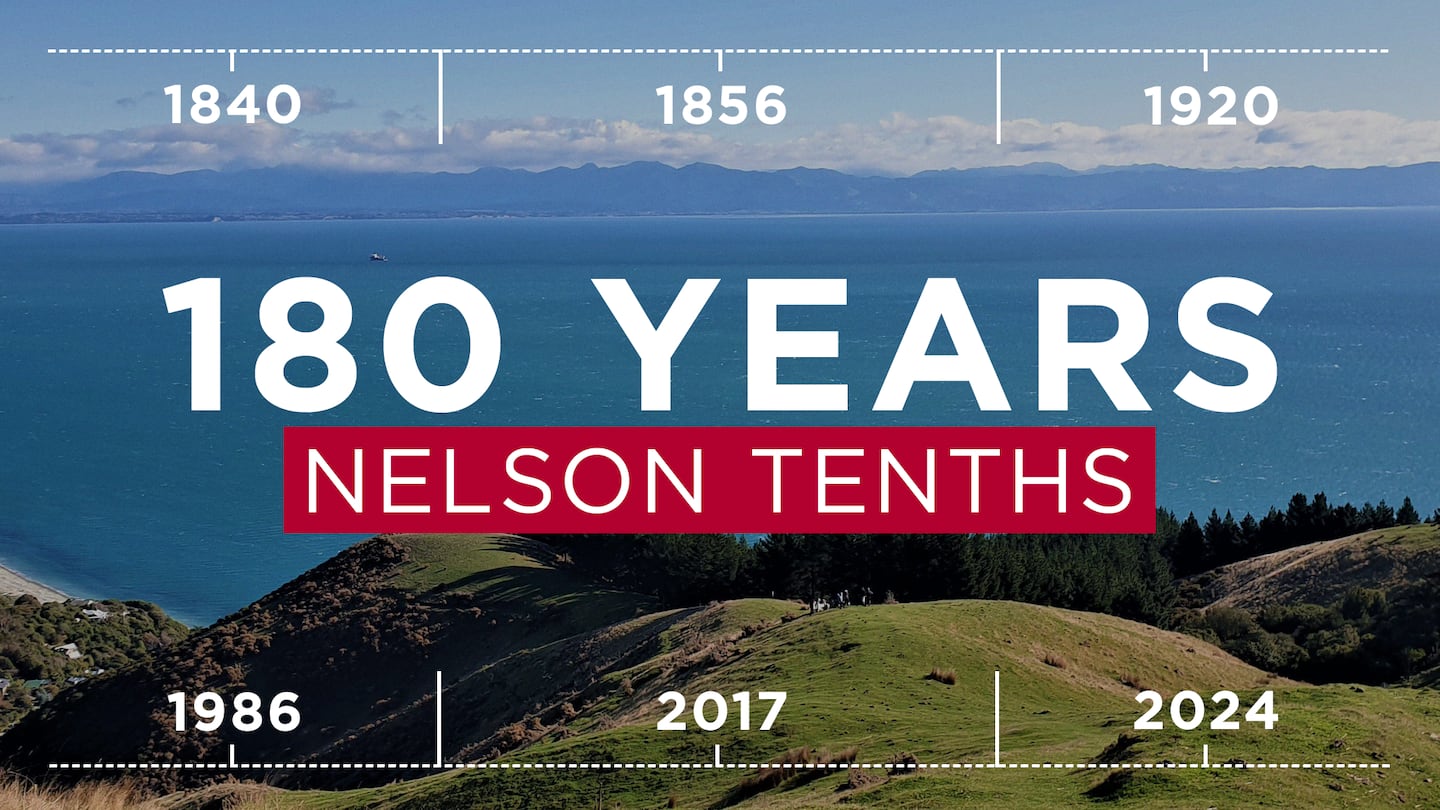

“We’ve been fighting this case in some form for more than 180 years. It’s time now for the Crown to do the right thing, honour its clear legal duty and enable us, finally, to turn our energy to the opportunity and healing that this resolution offers for our region.”

The 338-page High Court judgement, released today, outlines the extensive history surrounding the case.

Here, we revisit the history of the case to explain today’s decision, based on the outline of facts in Stafford v Attorney-General.

1820s - 1830s: Pre-colonisation

The local iwi of Te Tauihu o te Waka a Māui, the top of the South Island, had arrived in the region in the 1820s and 1830s.

These iwi, Ngāti Rārua, Ngāti Awa (now known as Te Ātiawa), Ngāti Tama and Ngāti Kōata, had migrated from the Tainui-Taranaki region.

Rore Stafford, who was the plaintiff in the Nelson Tenths case, is a kaumātua of Ngāti Rārua and Ngāti Tama descent, and a direct descendant of Ramari Herewini and her father Poria, who were both named as beneficial owners of the Tenths.

The Kurahaupō iwi (Ngāti Apa ki te Rā Tō, Ngāti Kuia, and Rangitāne o Wairau) already lived in the area.

1839: Creation of the New Zealand Company

A year before the signing of Te Tiriti o Waitangi, the New Zealand Company (NZC) was founded in Britain, and in May, Colonel William Wakefield sailed for Aotearoa.

The company sought to create a town to be called ‘Nelson’ and wanted to buy 200,000 acres of land from local Māori, which it would subdivide and sell to European settlers.

Central to the agreement was a guarantee between local iwi and the company that one-tenth of the land ceded by the Māori vendors would be reserved by the company and held in trust for the benefit of “the chiefs, their tribes and families”.

February 6, 1840: Te Tiriti o Waitangi

Te Tiriti o Waitangi was signed on February 6, 1840, with debate continuing to this day over the differences between the Māori and English texts.

The Land Claims Ordinance of 1841 rendered pre-Treaty land purchases null and void unless sanctioned by the Crown, leading to the appointment of Commissioner William Spain to investigate the New Zealand Company’s land purchases, while the 1840 agreement stipulated that the Crown would reserve the Tenths for Māori.

1841: The Kaiteretere hui

In 1841, Captain Arthur Wakefield met local rangatira at Kaiteretere to establish the Nelson settlement.

Since buying land directly from Māori was illegal, the company offered gifts worth £980 15s to confirm prior agreements.

The customary owners welcomed the settlers, seeing it as an invitation to coexist rather than a permanent land sale. Discussions may have included excluding Te Maatū forest from the sale.

Further meetings occurred in 1842 and 1843.

1841-1843: Selecting the tenths

In February 1841, the New Zealand Company announced plans for the Nelson settlement, allocating 221,100 acres, with 201,000 acres for settlers and 20,100 acres reserved for Māori.

Each allotment included one-acre town sections, 50-acre suburban sections, and 150-acre rural sections, selected through a ballot process that also applied to the Tenths.

In 1842 and 1843, 5,100 acres of Tenths were selected, leading to conflicts where both Māori and company officials were killed; many selected Tenths were reportedly over occupied lands such as pā, urupā, and cultivations, referred to as the Occupied Tenths, while rural Tenths were never allocated due to opposition encountered during attempts to survey Wairau lands.

1844-1845: The Spain commission

The Crown appointed Commissioner Spain to investigate the New Zealand Company’s purchases under the Kāpiti and Queen Charlotte deeds, with hearings beginning on August 19, 1844.

After the sole Māori witness, Te Iti, cast doubt on the company’s claims, the inquiry shifted to arbitration, resulting in the company making additional payments totaling £800 to various iwi.

On March 31, 1845, Spain determined that Ngāti Toa lacked authority to sell all land in Te Tauihu but found the additional payments addressed deficiencies in the original purchase, ultimately recommending that the company be granted 151,000 acres—significantly less than the requested 221,100 acres—while excluding pā, urupā, and cultivations from the Crown grant.

1845: Crown grant

On July 29, 1845, Governor Robert Fitzroy issued a Crown grant of 151,000 acres in Nelson to the New Zealand Company, explicitly excluding “pā, burial places and grounds actually in cultivation” as well as the “Native reserves” (the Tenths).

However, the company rejected the grant, citing dissatisfaction with the awarded acreage, as its proposed settlement required 221,100 acres, and the Wakefields felt the grant did not provide sufficient security of title due to the vague definitions regarding the excluded lands.

1846-1847: Massacre Bay Occupation Reserves

From 1846 to 1847, efforts to find suitable land for rural sections continued, with some land identified in western Blind Bay and Massacre Bay, though concerns about its quality arose.

Following Governor Robert Fitzroy’s departure, Governor George Grey negotiated the purchase of Wairau from Ngāti Toa, which included reserving a large area known as the Kaituna Reserve for Māori.

During this period, surveys in Massacre Bay led to the establishment of Occupation Reserves, which remained under customary title but were managed alongside the Tenths; part of the plaintiff’s claim pertains to these reserves, specifically whether their allocation was intended to replace the rural Tenths, raising questions about potential breaches of fiduciary duty.

1848: Crown grant

Negotiations for a Crown grant continued between the New Zealand Company and Governor Grey, leading to the issuance of the 1848 grant, which encompassed a large block of land in the South Island and included all land from the earlier 1845 grant, along with the Wairau land purchased by Grey.

Excluded from this grant were “pā, burial places, and [the Tenths],” with attached plans reflecting the 1842 surveys and Occupation Reserves, though the rural Tenths remained uncharted.

1850: company failure

In the 1840s, the New Zealand Company faced increasing financial strain, prompting the imperial government to enact the New Zealand Company Loans Act 1847, which provided a loan secured by the company’s land.

Under this act, any surplus land held by the company was to be held in trust for the Crown and returned if not needed for settlement, with ownership reverting to the Crown if the company surrendered its charter, which it did in 1850, resulting in the remaining land from the 1848 Crown grant being vested as domain lands.

The remainder of the 1800s

Between January 1845 and 1848, there was no formal appointee to manage the Tenths, with George Clarke Junior serving as a temporary agent.

In 1848, Lieutenant-Governor Edward Eyre appointed a new board of management, which governed until 1853 when Governor Grey replaced it with the Commissioner of Crown Lands.

The New Zealand Native Reserves Act was enacted in 1856 to establish a formal management system for the Tenths, allowing for the alienation of lands for Māori benefits. An amendment in 1862 empowered the governor to dismiss the commissioners and transferred certain powers to the Executive Council.

By 1882, the Tenths were vested in the Public Trustee, concluding the period of the plaintiff‘s claims, which allege that their value diminished due to various exchanges and grants since 1842.

In 1892, the Public Trustee sought to identify the beneficiaries of the Tenths, leading to a 1893 ruling by Judge Alexander Mackay that confirmed 253 descendants of the customary owners and established their interest in the Tenths’ income.

1900s: Transfer of ownership

In 1920, the Tenths were transferred to the Native Trustee, which later became known as the Māori Trustee. Following the Sheehan commission of inquiry into Māori reserved land in New Zealand, the remaining Tenths were vested in the proprietors of Wakatū under the Wakatū Incorporation Order of 1977.

Wakatū now holds these Tenths on trust for the Customary Owners, ensuring that the interests of the descendants of the original landowners are protected. This transfer aimed to address historical grievances related to land management and ownership among Māori communities.

1986: Waitangi Tribunal

In 1986, a claim over the Nelson Tenths was filed with the Waitangi Tribunal (Wai 56).

The Crown acknowledged several breaches of Treaty principles during the tribunal proceedings, particularly concerning the Tenths, and the tribunal issued its report in 2008.

Following this, negotiations between the Crown and various iwi settlement entities ensued, which were temporarily halted when a related proceeding was initiated in the High Court in 2010. Negotiations resumed, resulting in the Ngāti Kōata, Ngāti Rārua, Ngāti Tama ki Te Tau Ihu, and Te Ātiawa o Te Waka-a-Maui Claims Settlement Act 2014, which came into effect on April 23, 2014.

This act discharged the Crown from any liability related to “historical claims,” including those concerning the Tenths, although a preservation clause allows for the current proceeding to continue.

2017 - present

In 2017, the Supreme Court determined that the Crown had a legal duty to reserve the Tenths and instructed the parties to return to the High Court to assess any breaches, remedies, and Crown defences.

Subsequently, in 2023, a 10-week High Court hearing was held in the case of Stafford v Attorney-General to address these issues.

In June 2024, the government allocated $3.6 million of taxpayer funds in the Budget to prepare for an appeal against the High Court’s impending decision, even though the ruling had not yet been issued.

Today: victory

After 180 years, the High Court has today found in favour of the customary owners of the Nelson Tenths in its decision on Stafford v Attorney-General.