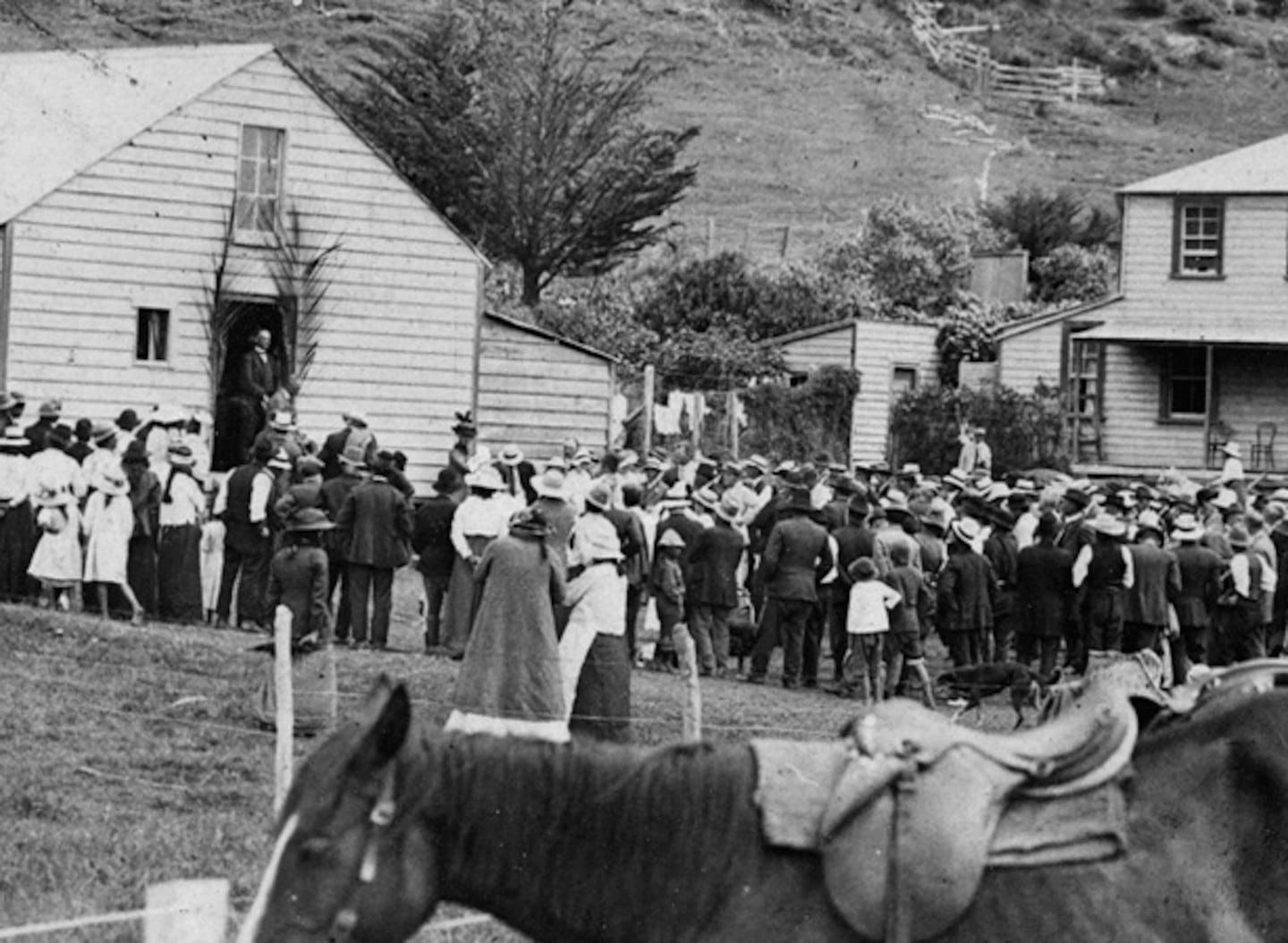

New Zealand’s oldest and longest-running specialist court has turned 159 years old. On October 30, 1865, the Native Land Court was created, a product of the Native Lands Act 1865. People today know it as the Māori Land Court.

The original intent of the court was to convert customary Māori land claims into legal land titles. However, the law had made sure a block of land, regardless of its size, could only have up to 10 owners. This meant the remaining Māori who occupied the land were not legally recognised as having rights to it. As a result, the recognised “owners” were able to manage or sell the land individually, often for personal gain.

Historian Dr Aroha Harris (Te Rarawa, Ngāpuhi), said part of the intent was for it to get Māori land into the hands of Pākehā settlers

“This is oversimplifying but the basic pattern is Māori land goes into the court, it’s just a matter of time before it transfers to the Crown, which is trying to get it into the hands of Pākehā settlers and that’s the basic pattern.”

‘Wartime strategies’

During the time the courts opened, was near the end of the civil wars in Aotearoa. The act and the court were introduced a year after the Waikato War.

In the same decade, legislation like the Native Schools Act, aimed at assimilating Māori into Pākehā society, and the Māori Representation Act, intended to reduce future racial tensions, offered far less representation for Māori compared with European voters, resulting in official neglect well into the 20th century.

For Harris, all of these and the court were “wartime strategies” against Māori.

“They have long-lasting impacts on Māori and, if you ask me which one thing most unravelled Māori society, I would say the Native Land Court, that would be my answer.”

In 1860, Māori held 80 percent of the land in the North Island. Just 20 years later, this dropped to 40 percent, with eight million acres passing into European ownership due to the Native Land Court and various land laws. By 2000, more than a century later, Māori land ownership had fallen to just four percent.

“The court had this illusion of being okay and being legitimate and being accepted by Māori because it had this legal process behind it but it’s a legal process that was designed for the wholesale transfer of Māori land to Pākehā settlers,” she told Te Ao Māori News.

Harris said it was easier for Māori to sell rather than keep the title of ownership.

“There [were] some great examples of Māori farming and that could have continued. But Māori couldn’t raise capital because investors didn’t want to invest in them, [and] banks didn’t want to lend to them.

“Māori were excluded from access to government funding until Āpirana Ngata got involved in the 20th century but, by then, a whole lot of damage had been done.”

Many Māori would rack up debts when having their cases heard in court, with some hearings lasting months. This meant after when it was all over, some would have to sell parts or all of their land to pay off the costs.

Feeling the impacts in the 21st century

A number of Māori people across the motu still own their land, either by retaining it or through having it returned.

Harris and her whānau own a bit of whenua in the Far North.

“Anyone who owns Māori and now knows how frustrating it is to deal with our land, how difficult it can be, especially if you’ve got small holdings.

“You have to do so much work and deal with so many different rules and regulations just to hold on to your property.

“You don’t get that with general land titles such as for the sections that some of us own in the cities, where the title to our land is very clear but the title to our Māori land is a complete mess.”

She spoke about the complications and resources needed to maintain and keep her whānau land where her grandparents’ whare lies.

Harris admitted to Te Ao Māori News that she felt a bit paranoid about the land being confiscated from the Crown.

“I would love to kind of not be paranoid about holding onto the land. But the Crown has got a track record and it’s not a good track record and we’ve kind of got generations who’ve felt pummeled by Māori land legislation.

“There’s a bit of wanting to relax and have some trust that things have changed enough that our land isn’t under threat of being taken again but then you have to think about that in relation to this long history of land being taken over and over again.”

Land Courts u-turn

In 1954, the Native Land Court was renamed, replacing “Native” with “Māori”. However, this wasn’t the only shift. As Māori Land Court Chief Judge Caren Fox (Ngāti Porou) explained to Te Ao Māori News, its history is “one of transformation”.

“Originally known to Māori as ‘te kooti tango whenua’ for its role in the 1800s in individualising land title and enabling the loss of Māori land from their ownership, the work of Māori landowners alongside successive governments have seen it evolve into a court that acts, in the words of former chief judge Tā Taihakurei Durie, ‘as a forum to facilitate and enable the utilisation of land held in multiple ownership, to facilitate owner-management of lands, and to settle differences arising within the body of owners’.

“While ensuring that this land is retained by their owners, their whānau and hapū and can be passed down to future generations. All decisions concerning the practical use of the land are now made by owners, or their trustees or their committees of management, in accordance with the principle of rangatiratanga as set out in the preamble of Te Ture Whenua Māori Act 1993.”

Throughout its history, the jurisdiction of the Māori Land Court has evolved. In 1894, the court gained authority to grant probate and letters of administration for Māori but this was revoked in 1967. The Native Land Act 1909 empowered the court to issue adoption orders, though this responsibility shifted to the Magistrate’s Court with the Adoption Act of 1955. The Māori Lands Amendment Act 1967 further limited the court’s authority in certain areas.

The court’s current jurisdiction stems from the Te Ture Whenua Māori / Māori Land Act 1993, which significantly expanded its authority.