As the government looks to amalgamate several laws under one process with the Fast-Track Approvals Bill, a new generation of kaitiaki - guardians, and climate advocates - is calling for indigenous knowledge and Te Ao Māori worldviews to be central in decision-making.

One Kaitiaki is soon-to-be mum Te Huia Taylor of Ngāti Te Ata. She recently helped lead Māori engagement with Auckland’s Climate Plan - Te Tāruke-ā-Tāwhiri. However, revitalising Mātauranga Māori among her iwi and tangata whenua is her passion, with a centuries-old tradition like raranga (weaving) being one simple practice that allows her to connect with her environment.

Taylor says, “I au e mahi ana ēnei mahi ka tino kite he hononga nui ki tō te mahi raranga, ki tō tātou taiao. Mēnā kāore e tika ana ngā āhuatanga taiao, e kore e puta mai te hua o te harakeke, e kore e pai tō mahi i āu mahi raranga mēnā, he kete tēnā, he korowai rānei tēnā. Nō reira, āe me ora te taiao kia puta mai ngā hua, kia pai ai ā tātou whakatinana tonu i ngā tikanga raranga.”

“As I do this type of work, I can really see the link between weaving and our environment. If the environmental conditions aren’t healthy, the flax won’t grow properly. Then it’s reflected in your work when you weave it, whether it’s a flax kit or a cloak. So yes, the environment must be healthy so our weaving practices can be adhered to.”

0 of 9

Ngāti Te Ata lived in the area of Tāmaki Makaurau for over 40 generations.

From the Tupuna River of Waikato to the lands spread between Te Mānukanuka o Hoturoa - the Manukau Harbour and Te Tai o Rehua - the Tasman Sea, sits Āwhitu Peninsula. It’s a place where Te Huia’s tribe of Ngāti Te Ata has lived for over 40 generations.

Taylor says, “Ko te tirohanga o Te Reo Māori ko te taiao, i ahu mai tō tātou reo, tō taua reo i tēnei taiao tonu. He iwi wai mātou, mēnā ka tirohia tō mātou rohe, kua karapoti tō mātou whenua ki te wai.”

“The intrinsic value of nature is reflected in the Māori language, our language comes from this environment. We are a water tribe. If you look around our lands, our lands are surrounded by water.”

However, in just a few short generations everything changed. Intensive farming on confiscated whenua has polluted their waterways and food sources; and their food bowl of Manukau harbour turned into Auckland’s sewage bowl.

There are also consequences of an enormous iron sand mining operation and coal, burning to fuel the sprawling NZ Steel mills at Glenbrook, just across the water from their marae.

“The saddest thing about it all is that I don’t notice it every time I come to the marae. That’s how long it’s been there and that’s how long the mining company has been part of our history,” Taylor says.

The ancient burial ground of Maioro mined since 1968

Further south, situated at Te Puaha o Waikato - the mouth of the Waikato River - is their ancient burial ground of Maioro. Archaeologists carbon dated the pā site at AD.1042. It’s one of over 150,000 acres of iwi land confiscated by the Crown and on top of that, the sacred site itself has been mined since the 1960s.

“I think about my tūpuna, my mum’s generation, who have fought so hard to try and stop that mining company from mining our wāhi tapu (sacred places) mining our kōiwi (human bones) engari auare ake (but to no avail). There are no results (from the Waitangi Claim 8 - Wai 8) that have come from it. Yeah, it’s pretty heartbreaking really,” Taylor says.

Findings from Wai 8 claim led by Nganeko Minhinnick paved the way for the Resource Management Act 1991

Her kuia was the late Dame Nganeko Minhinnick. Minhinnick’s fight and struggle for her land and people began at 11 years old.

But it was later in life in 1982 the Ngāti Te Ata and Te Waiohua elder led a landmark Waitangi Tribunal claim - Wai 8. The findings from it paved the way for the Resource Management Act 1991, a key piece of legislation that has set out how Aotearoa should manage its environment.

Rangatahi attend inaugural Climate Change Wānanga

0 of 6

In the first week of June this year, veteran campaigner Mike Smith held a Wānanga, Take Āhuarangi - Hui-a-Rangatahi Māori at Ōrākei marae, explaining climate change to rangatahi and bringing Mātauranga Māori - indigenous knowledge (natural resource management systems such as rāhui) to the fore.

The Ngāpuhi and Ngāti Kahu descendant is astonished by kids coming through the Kōhanga Reo and Kura Kaupapa movements, knowing Mātauranga Māori and practicing Māori values.

“Just by our Kaupapa Māori, you know, listening to these kids coming through the Kōhanga, Kura Māori, the Wānanga, they’ve already got it in their hearts and souls. They know the difference between right and wrong. They know the difference between good and bad. And they don’t need me to tell ‘them what’s going on,” Smith says.

Mike Smith leads a landmark case against NZ’s biggest polluters

0 of 5

And on behalf of rangatahi and so many others, Smith is leading a landmark case against what he claims are New Zealand’s biggest polluters - Fonterra, Z Energy, and Genesis Energy to name a few. And it’s gone all the way to the Supreme Court.

Smith says, “The thing about court actions is that it’s an action that only a few players get to play. It’s an exclusive sort of thing but, from what I understand about the law, is the law is often dragged kicking and screaming along by public sentiment of the time. So for example 50 years ago, if women wanted to get women’s rights, they would have struggled because the mood of the public didn’t support that. Equally Māori rights, equally gay rights.

“But when the mood of the people shifts, it drags the courts along with it. And so we all need to be part of that. That’s something that we can all do. You know, I’d like to see the mobilisations that are happening at the moment to also have climate messaging in it. So it sends a signal to the politicians.”

Over 20,000 attend protest ‘March for Nature’

And on June 8, New Zealanders answered that call at the March for Nature. Thousands took to the streets of Auckland to protest against climate change, deep sea mining and use of fossil fuels. There was real anger and deep concern over the coalition government’s Fast-Track Approvals Bill, which is all about speeding up the consent process and cutting red tape.

A member of the public said: “Fast-track proposals will ruin this country for my children and everyone else’s children.”

Cindy Baxter from Kiwis Against Seabed Mining said: “One of the worst projects would be the seabed mining project in the South Taranaki Bight. They’ll be digging up 50 million tonnes of the seabed every year for 35 years.”

Forest & Bird’s Nicola Toki said the best thing the government could do “is chuck it in the bin, it is poorly drafted, it doesn’t have the right controls”.

The government is one of the major threats to Māori people, says Mike Smith

And Smith is of the view that this government here is probably one of the major threats to Māori people in terms of climate.

“You can see it on their policies. They’ve been rewinding or pushing back any of the positive climate policies in recent times. Korekau he whakaaro mō ngā rangatahi, korekau he whakaaro ki te taiao. There is no thought for our youth, no thought for the environment,” Smith says.

The Government wants to streamline the process

Put simply, the Fast Track Approvals Bill is looking to make it easier for people, businesses, and councils to deal with the likes of the Resource Management Act, Conservation Act and Crown Minerals Act. The government wants to streamline the process.

At the bill’s first reading, the minister leading the change, Chris Bishop said he was very proud of this legislation.

“I have believed and the coalition government has believed for a long time now that it’s too hard to do things in this country, and it’s not just my belief that that’s the case. We know from the facts that it is.

“We spend $1.3 billion in resource consent fees per year. It is just too hard to do things — too hard to build houses, too hard to build roads, too hard to build public transport, too hard to build geothermal and wind power stations, too hard to build mines for the future, too hard to get aquaculture projects up and running — and this is part of the government’s process of unclogging that.”

But rather than letting the experts decide, the plan is to leave it to three government ministers, Infrastructure Minister Chris Bishop, Transport Minister Simeon Brown and Regional Development Minister Shane Jones.

Jones also has not held back about the legislation for mining being turbocharged. He told the Breakfast show: “We are opening up for oil and gas, we are changing the law. We are opening up the DoC estate in appropriate places in Taranaki. We are not taking a risk with a unicorn-kissing approach that characterises the left-wing approach to energy.

Is the government serious about its targets to limit global warming to 1.5C?

But experts warn New Zealand’s global reputation is on the line. The government’s ambition for reducing carbon emissions to limit global warming to 1.5C is seriously at odds with proposals to restart drilling for fossil fuels.

Either way, it’s cold comfort for Ngāti Te Ata and Te Huia Taylor.

Taylor says, “Hei aha to hiahia ki te whakatere i ēnei mahi maina, whakakorengia ngā mea kua tīmata kē, kua kitea au i ngā pānga taiao, ngā pānga wairua, ngā taumahatanga katoa kua tau mai ki runga i a mātou o Ngāti Te Ata, ā, kei te pērā tonu. Me hia rawa ngā tau ka rongo mātou i ngā taumahatanga? Kua nui.

“Never mind fastening these activities like mining, just finish up what has already begun. I’ve seen the effects it has on the environment, its spirit, the burden of it all that has been put on us, of Ngāti Te Ata and it is still the same. How many more years do we have to bear the burden? That’s enough.”

Government shortcuts on environmental protection and rights

India Logan-Riley is another wahine Māori who is taking up Māori and Indigenous concerns over what they see as government shortcuts on environmental protection and rights.

“I mean for me climate justice is really about dismantling toxic systems of power and creating community-led ones that honour life and sharing and generosity and those values that we hold within Te Ao Māori,” Logan-Riley says.

Already Logan-Riley has witnessed the impacts of climate change on her community first-hand with evacuation in 2016 due to severe drought and wildfires; and most recently Cyclone Gabrielle in 2023. But it’s knowing her home and family will be underwater in her lifetime is what really drives her activism work.

Land back, Oceans back

In 2021, Logan-Riley addressed the COP26 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow, Scotland, with an indigenous perspective.

Excerpts from her speech: “I cannot put it more simply than we know what we are doing, and if you are not willing to back us or let us lead, then you are complicit in the death and destruction that’s happening across the globe…”

“Land back, oceans back. This is an invitation to you. This COP, learn our histories, listen to our stories, honour our knowledge and get in line or get out of the way...”

Tino Rangatiratinga combined with knowledge systems and connection to place or environment - that was the message and still is. India Logan-Riley tributes advice given to her for that speech with a known Uncle from her marae of Waipatu and iwi of Ngāti Kahungungu.

Colonial capitalism set us up for Climate Change

“As Uncle Moana Jackson said, if you don’t look to the whakapapa of something, then you can’t actually really know what the solution should be. And so, in knowing that colonial capitalism set us up for climate change, that’s what we have to address to really grapple with climate change,” Logan-Riley says.

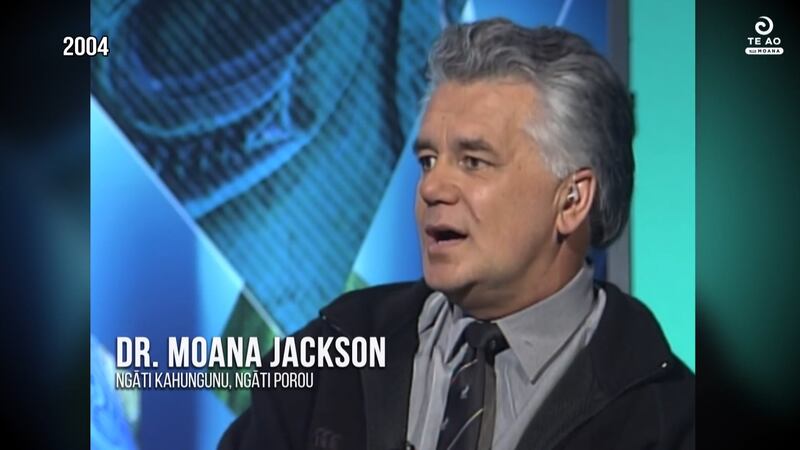

The late Dr Jackson was a lawyer and staunch Māori rights activist. He also strengthened Indigenous rights globally through his work on the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Alignment between the lifting of Te Tiriti rights - with fossil fuel companies & foreshore and seabed confiscation

Logan-Riley says he was pivotal in bringing to light the meaning behind the 2004 foreshore and seabed controversy. “He’d raised a really good point that basically drew a connection between fossil fuel companies looking for oil and gas off the coast here and then the foreshore and seabed confiscation happening. And that there being a very clear alignment between a lifting of Te Tiriti rights.

“He was heavily involved with the foreshore and seabed space. And I think that being a really important part of Māori activism as well, is that intersectionality and that intergenerational aspect where we get to learn from those who fought the hard yards before us, and that they can mentor us and teach us and help us do better,” Logan-Riley says.

Globally Indigenous people make up 6.2% yet are on the front lines of climate protests

0 of 7

Though indigenous people make up just a small part of the world’s population, indigenous concerns have helped motivate global protest. Indigenous have been on the front lines and mining has been the most common cause of environmental conflicts.

60% of indigenous peoples’ lands globally are threatened by potential expansion

Globally, 2.5 billion people depend on just a quarter of global lands and ecosystems held by Indigenous people for food, water, air, quality, and more. Yet a recent study shows 60% of indigenous peoples’ lands are moderately to highly threatened by potential expansion of oil and gas production, renewables, mining, commercial agriculture, and urbanisation. These concerns are front and centre for Māori concerns over man-made climate and the current Fast-Track Approvals bill breaching Te Tiriti o Waitangi. And earlier in May, Ngāti Toa descendants rallied together to Parliament directly about their concerns.

Concerns Fast-Track Approvals bill will breach Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

Helmut Modlik of Ngāti Toa says, “To engage with us respectfully, honour the settlement in spirit and as well as in the letter.” Another iwi member Kahu Ropata says, “Hōmai he wā kia kōrero te take, kāōre a Ngāti Toa e whakahē ana i te whakawhanake tāone, kāo. Kia pāhemo ngā taonga o te taiao.” “Give us the time to discuss the issue, Ngāti Toa are not against the development of our towns, no. But we don’t want to kill off the flora and fauna.”

Mike Smith says, “We don’t have a government that’s responsible enough to deal with the issues in front of us. They’re not here protecting our Papa (Mother Earth) and protecting it for ourselves, our children in the future they are only thinking about themselves and today.”

Traditional practices and climate are inextricably linked.

Back at Tāhuna marae in Waiuku, Te Huia Taylor sees the traditional practice of weaving and concerns over climate as inextricably linked. Both need protection and the clock is ticking. Raranga - weaving alone holds a range of Māori values and concepts, it’s associated with Hineteiwaiwa, one of the many deities in Māori cosmology linked with the rhythms of life - nature.

Taylor says, “Ka tino kite i te hōhonutanga o te whakaaro o te Māori. Mēnā ka tirohia i a Hineteiwaiwa koia te atua o te marama, o te pēpi i a koe e kōpū ana, otirā ngā mahi raranga nei. Nō reira ka whakaaro he aha pea ngā hononga o ēnei mea e toru. Ko te marama tērā i a rua tekau mā waru rā, ka huri ka huri. He rite tonu tērā ki te āhuatanga o te wahine, ka kōpū te wahine, a, ko te kahu tuatahi o te tangata ko te kōpū, i a koe ka puta ki te ao nei, anei ngā mahi hei whakakākahu i te tangata.”

You can see the breadth of the connection in a Māori worldview. If you look at Hineteiwaiwa, she is the deity of the moon, childbirth, and weaving. So we think about what the connection is that these three things have. Well, the moon has 28 phases, that’s the rhythm of the moon cycle. It is the same aspect with women and their menstrual cycle. As the woman conceives, what cloaks the fetus is the womb. And when you are born into this world, here is the work to do, to clothe a person.

Te Ao with Moana asked Te Huia Taylor what her hope is for her people of Ngāti Te Ata when looking at legislation like the Fast-Track Approvals Bill.

Taylor referred to a tongikura - a quote from the late Māori King Tāwhiao - saying, ‘E kore tēnei whakaoranga e haere ki tua o aku mokopuna’. We must provide our children and their children a better platform than the one we inherited. So when I think my kuia’s generation started this, so this take is meant to finish with me and it shouldn’t go down to pepi, and we should be able to resolve it and start to progress the iwi and see real steps forward for the iwi and my big hope is that she doesn’t have to deal with any of it and that we can resolve it in my time.”

The commodification of the land, and resources has fueled the climate crisis & disconnection, says Logan-Riley

India Logan-Riley says “It’s the commodification of the land and resources that has fueled the climate crisis and that disconnection. And we just have to sit with the discomfort of that and try and figure out our pathway through rather than going, ‘oh, well that’s the way the world is’. And so we gotta embrace that changing and just try and figure out what a pathway forward that is really grounded in our values.”

Mike Smith says, “We are staring down the barrel of a global catastrophe. It’s an, it’s an emergency. I don’t see the police cars going down the road with the lights, flickering or the planes flying overhead to fight the climate war. Mā wai e tū hei tiaki i a tātou nei rawa, rātou? te kāwana? Kāo.” Who will stand to protect these natural resources? the government? No.

The select committee report is due on October 18. If passed, a standalone Fast-Track Approvals Act could become law later in 2024.