A couple who separated after a long-term relationship and moved to different parts of the country were at odds over who should have custody of their children, who were initially raised in a te ao Māori-focused household.

The father was worried about the mother’s unstable housing situation, while the mother was concerned about the children not being immersed enough in Māori culture.

Now a judge has decided they are better off with their mother, ruling in a Family Court decision released this week that their cultural identity won’t be preserved or strengthened in the custody of their father.

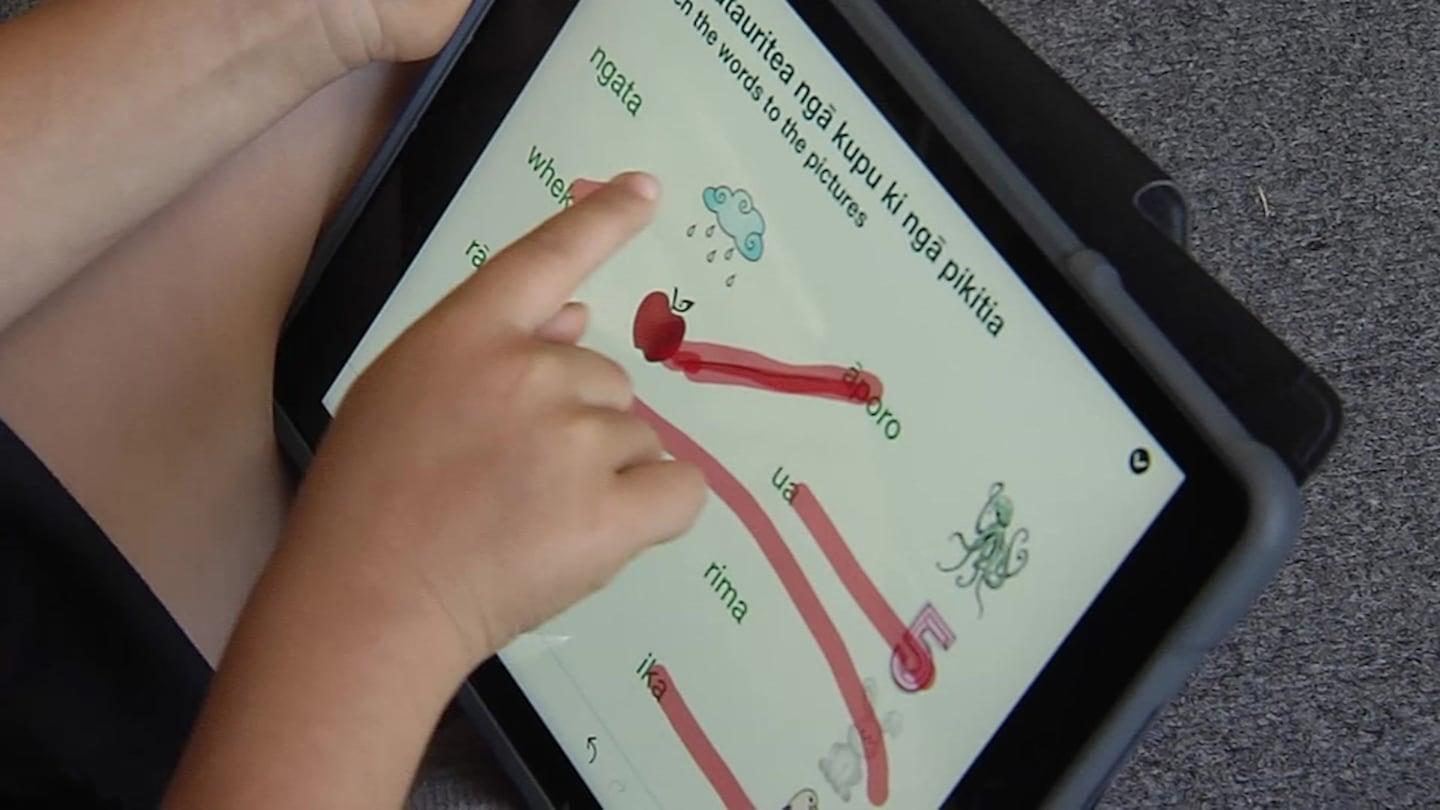

The couple, Rachel and Jacob* had several children who were born into a predominantly Māori-speaking home and were educated in kōhanga reo (Māori immersion kindergarten) and later kura kaupapa (Māori immersion school).

Rachel was a fluent speaker, while Jacob described himself as a “Kiwi New Zealander” and had a limited but growing knowledge of te reo, and grew up with a “close affinity” to the Māori worldview. He had an iwi affiliation, but Rachel claimed he never mentioned this when they were together.

Their relationship collapsed when, according to Rachel, Jacob became physically abusive during an argument. He left the family home, moving hundreds of kilometres away to live alone with his new partner.

For a short time, all of the children were solely in the care of their mother until Jacob requested unsupervised contact. Oranga Tamariki found the children would be safe in either household, and the request was granted.

Rachel later placed three of their children in Jacob’s care on what she believed was a temporary basis, while she tried to find more suitable housing. An older child remained in her care.

Eventually, Rachel and Jacob agreed to continue with the same agreements for the older children but both wanted day-to-day custody of the younger two.

The younger children themselves had different views on where they wanted to live - one wanted to stay with dad, and the other with mum. Whilst “highly relevant”, Judge La-Verne King ruled the children’s best interests were more important than their own view.

In court, Jacob claimed that Rachel had moved house multiple times and he was concerned about stability for the children. He worried that if the younger children were placed in Rachel’s custody after two years with him, the older child he had custody of would struggle without the younger siblings around.

But Rachel rejected the stability concern and counter-claimed that the younger children’s declining use of te reo and inability to attend cultural events in the care of their father restricted their cultural needs.

In assessing the case, the judge found cooperation between the parents was limited. Rachel never consulted with Jacob when enrolling the older child in her care at a local school, nor vice versa when Jacob enrolled the younger children at a primary school in his area.

But most concerning to the judge was Jacob’s decision to enrol the younger children in a normal kindergarten shortly before they started school. Both children had attended kohanga reo since the age of six months and were accustomed to Māori-immersed education.

“The impact of [Jacob’s] unilateral decisions is that the [younger children’s] use of and ability to kōrero Māori has declined significantly,” Judge King wrote.

Whilst the older children speak te reo fluently, the younger children in Jacob’s care primarily spoke English.

Rachel also alleged Jacob monitored the children’s video calls with her despite her being allowed unsupervised contact, while Jacob alleged Rachel had breached the court-ordered care arrangements by failing to return the children to his care on time during school holidays.

Children’s cultural needs ‘not preserved’ - judge

The judge was required to assess the case based on a variety of factors, including continuity and stability for the children, their cultural needs and their safety.

Continuity of care rested clearly in favour of leaving the two younger children in Jacob’s care, but his actions in enrolling them in a general kindergarten and unnecessarily monitoring their video call interactions with their mother hampered their development.

Rachel had also submitted that the children were unable to attend important cultural events such as her iwi’s festival and Matariki celebrations.

“From a tikanga perspective, a child’s attendance and participation at whānau, hapū or iwi activities will not only preserve, but strengthen that child’s relationship with whānau, hapū or iwi,” Judge King ruled.

The judge also found the children have limited opportunity to converse in te reo within Jacob’s home, and their class at the school he enrolled them in was bilingual - not solely in te reo.

“The treaty principle of active protection is particularly important and requires the court to protect these children’s ability to not only speak Māori but to thrive in a Māori speaking environment.”

Judge King said both Jacob and Rachel were good parents, but their poor communication over the time they were separated was to the detriment of their children.

The impact of Jacob enrolling the children in a general primary school without consulting their mother was a significant change in their upbringing.

“The impact on [the younger children], as tamariki Māori, is that their identity, in terms of their culture and their language, has not been preserved nor strengthened. Nor will it be if they remain in their father’s care”

She also found Jacob’s concerns around the stability of Rachel’s housing were not well founded, and that his insistence on monitoring their video calls with her was not required.

The court ordered that the two younger children were to be placed in the day-to-day custody of Rachel, while Jacob would have custody during half of the school holidays. The arrangements with the older children remained as is.

Cultural needs a significant consideration - lawyer

Speaking to NZME generally, Auckland-based family lawyer Jeremy Sutton said the vast majority of custody disputes are settled outside of court - a case in the Family Court is the last resort.

He said disputes where parents live long distances from each other are rare but can make for a very difficult assessment for the judge, especially if there a whānau, hapū or iwi considerations tied to a particular area.

“The judge is required to look at what the best interests of the child are, and the child’s view comes into that, depending on their age.”

“The judge is required to look at a range of factors involving the child; what protective factors do they have, who is around them, have they been in that environment for some time, and in some situations, cultural factors become very important.”

Cultural considerations are a stated factor in the law, meaning the judge is required to consider their connections to hapū and iwi and their own cultural identity.

“In particular parts of the country where extended family are there, that can be an important consideration. The court is going to look at each case and decide the relevant factors, and the weight applied to those factors.”

“The judge can give as much weight or as little weight as the judge wants to give.”

*Names have been changed by the courts to protect identities.

Ethan Griffiths covers crime and justice stories nationwide for Open Justice. He joined NZME in 2020, previously working as a regional reporter in Whanganui and South Taranaki.