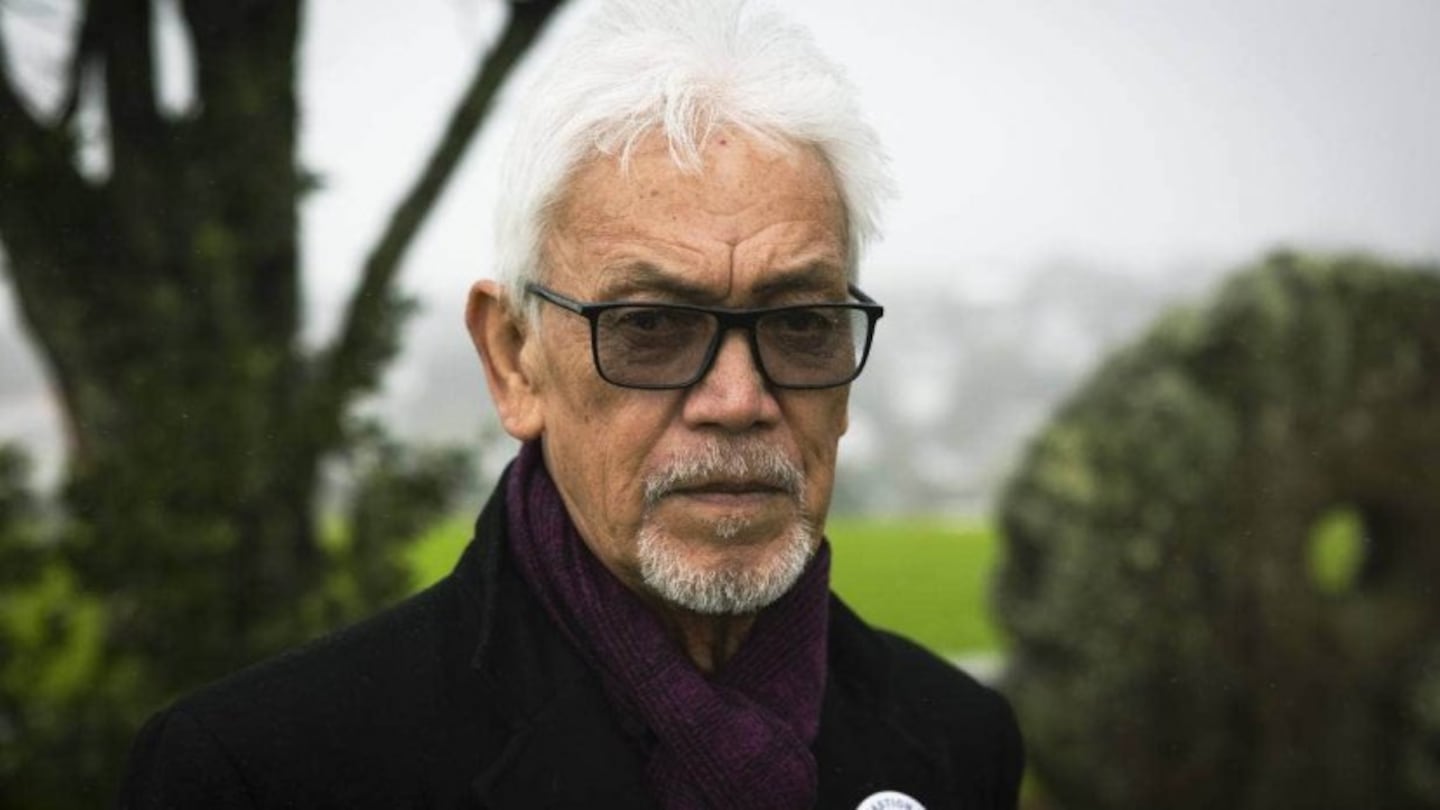

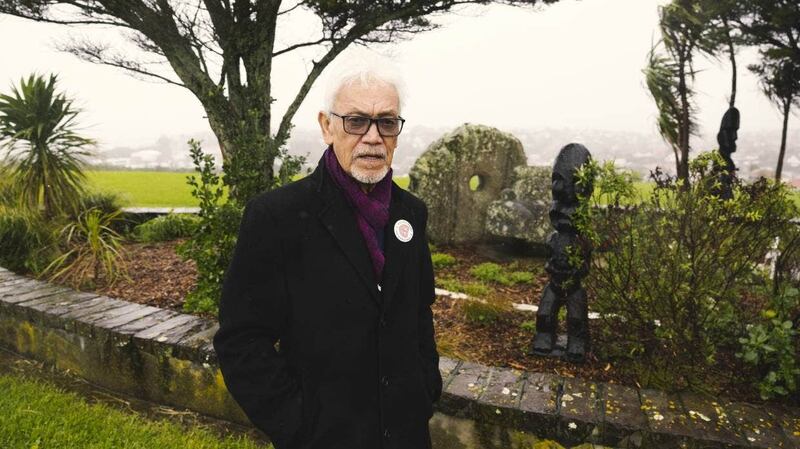

It’s been 45 years since police stormed Takaparawhau, arresting more than 200 people, including Te Aroha Alec Hawke. Ricky Wilson / Stuff

By Katie Doyle, Stuff

A group of 25 friends readied themselves as hundreds of police constables and army personnel filed on to Takaparawhau/Bastion Point, in Auckland.

Colloquially known as the “kids from Boot Hill”, they gathered in front of a memorial to a little girl called Joannee, who had died during the preceding 506-day occupation.

Among those surrounding the memorial was Joannee’s dad, Te Aroha Alec Hawke, who warned the police not to destroy the wooden structure.

The Boot Hill kids were arrested that day. Police tore down almost everything in their path – but didn't touch the memorial.

Boot Hill

There are a few schools of thought about the origins of the Boot Hill nickname but Hawke reckons it probably dates back to the burning of the Ngāti Whātua village at Ōkahu Bay.

It had been on the Crown radar since the 1920s and was considered a slum by those in power, according to Te Ara.

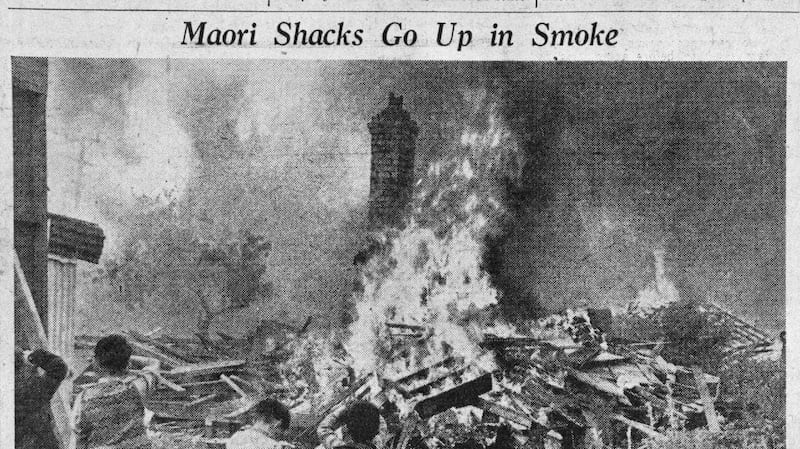

In 1951, the government forced Ngāti Whātua from the land and a year later razed the village ahead of a visit by Queen Elizabeth.

Ngāti Whātua whānau were relocated to state homes in Kitemoana St, devastating many, including one man who the Waitangi Tribunal said threw himself back into his burning whare.

“We were booted up the hill,” Hawke says.

Boot Hill would become a trademark and Hawke remembers taxi drivers using the name over their radio systems in the 1960s.

The emergence of gangs in Auckland marked another key moment in the Boot Hill history, because it solidified links between the kids growing up around Ōrakei, Hawke explains.

Burning of the Ngāti Whātua village at Ōkahu Bay. Source / Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections

“Headhunters in GI [Glen Innes], there were a couple of Black Power clubs being formed in Mt Wellington, the KCs [King Cobras] in Ponsonby and, earlier on, the Storm Troopers in South Auckland.

“The oldest of our group came around and said, ‘We're not going to patch.’ That’s how it started. We’re going to be a fraternity of cousins.”

They promised not to commit petty crimes and said if they were going to get into a fight, it would be against the Crown.

The struggle begins

The Takaparawhau occupation began in January 1977 when the whenua looked far different from the well-manicured reserve it is now.

Long grass covered the paddock and Hawke remembers his whānau and the Boot Hill kids having to cut through it to find a spot to make a cup of tea.

“We lit a fire, put the billy on and the fire never went out. Then they wanted a shelter, so we scoured the hill and our houses down at Kitemoana St, and we found a couple of tents,” Hawke says.

A caravan was brought on a few nights later, with a tent city slowly emerging under the summer sun.

Karakia would ring out every morning and night and Hawke would spend time learning about the history of Ngāti Whātua and injustices within central Auckland.

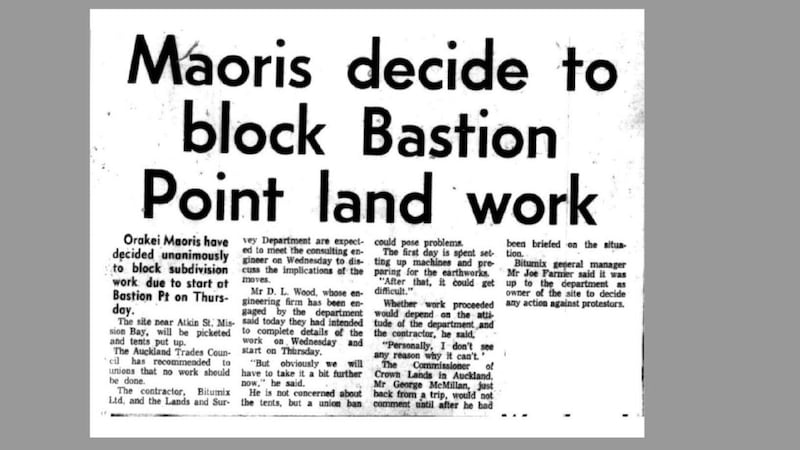

“We were always under the auspices of the Ōrākei Action Committee … born out of Ōrakei Marae when they informed our kaumātua that they were going to fight the National Party and Robert Muldoon's plans to build high-rise houses.”

Three happy months went by at Takaparawhau but the weather soon cooled and the kids of Boot Hill knew their tents weren’t going to be sufficient for winter.

A headline from the Auckland Star newspaper in 1977. Source / Stuff

As luck would have it, Whina Cooper was visiting and knew of someone with a hefty supply of wood to spare.

Three trucks were sent out, and all came back filled with kauri, tōtara and rimu.

“A meeting house was designed and Te Arohanui was built over a period of five months,” Hawke recalls.

“There was more wood … so people who had a longer-term view started to build, over their tents, corrugated iron houses.”

During the first summer, a group of what Hawke describes as travelling hippies arrived to offer their support.

They helped build a camp further down from the main site, with the aim of creating a barrier against any bulldozers that might show up.

It was dubbed “camp-run-amok” and those who lived there had open and free views about the world – possibly a bit more free than most others at the occupation.

“Our main committee decided that they had to pull it down, and come up. So there were a lot of tears … winter was coming and we had to consolidate.”

As his mind drifts back to that time, Hawke thinks of the Boot Hill whānau who helped make the occupation what it was.

While brother Joe Hawke may have been the face of the occupation, it was a Hawke family affair.

And it was Hawke’s mother and father – Piupiu and Eruini – who declared the occupation would remain non-violent, no matter what.

“My father, he was a member of the 1951 wharfie strike … so you had a working man's point of view. He always stood up for the working man,” says Hawke.

“My mother was salt-of-the-earth Ngāti Whātua … she was instrumental in teaching all of us about the history of the locals.”

Piupiu and Eruini took their non-violence view to the Ōrākei Action Committee, ensuring it spread throughout the ranks, Hawke says.

The Rameka whānau also played a key role in the occupation. Like the Hawkes, they were Boot Hill hardcore, with Mike and Roger Rameka both sitting on the Ōrākei Action Committee, says Hawke.

Alongside the politics, Takaparawhau was a hive of art, music and creativity.

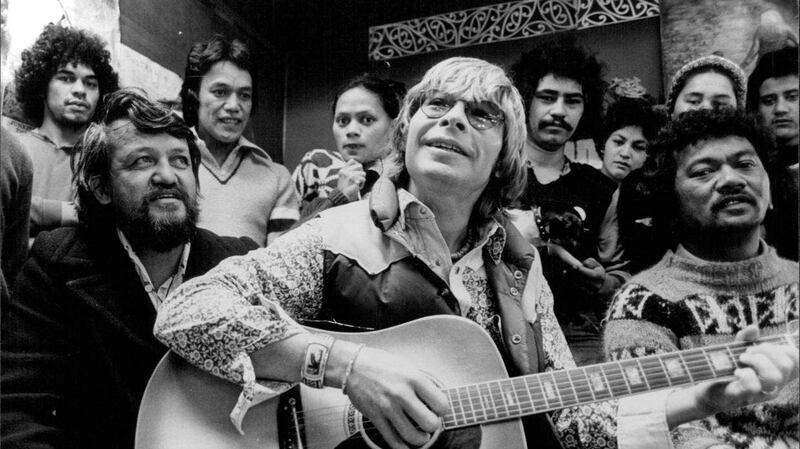

Fundraising concerts were held and American country singer John Denver even paid a visit while in town for a concert.

“He graced us with his repertoire of songs that he was going to sing at the concert. I think there were about five or six … he brought the house down. It was just like being in a studio, his voice was so, so good.”

John Denver paid a visit to Takaparawhau while touring in New Zealand. A young Alec Hawke stands behind him. Photo / Trevor Coppock

But the happy times would come screeching to a halt in September 1977 when a fire claimed the life of Hawke’s five-year-old daughter, Joannee.

“It was devastating. I wouldn’t want to put anybody through that.”

It nearly broke the occupation and saw Hawke and then-wife Mero leave for a time as they coped with their grief.

For three months the pair drove and drove and drove, stopping in at communities throughout the South Island along the way.

When they returned, the atmosphere of the occupation had changed. The fun was still there but a stark realism had set in, he says.

Hawke’s father, Eruini, constructed a memorial to the little girl, complete with a wooden bridge, water feature and garden.

Life at Takaparawhau continued, until May 25, 1978, when everything was literally ripped away.

Ugly scenes

After 506 days, the Takaparawhau occupation ended in ugly scenes involving police and army personnel.

“The Boot Hill hardcore – we advised the police that they better not do anything to the memorial.

“We surrounded Joannee … all 25 of us were eventually picked off and we went peacefully. They destroyed everything except the memorial.”

Cats, dogs, pigs and chickens were seized, and Hawke reckons that while the first three were all returned, no-one saw their chickens again.

Police remove a protester on May 25, 1978. Source / Auckland Star Historic Collection

The defining moment of the day for Hawke came when he was standing alongside his brother, Rex, and friend Dilworth Karaka. They watched on as a police convoy crossed the Auckland Harbour Bridge.

A plan to derail the cars had been vetoed by the occupation leadership, who decided to let the police on peacefully.

Hawke would later find himself near the meeting house, where his parents and many others were gathered. “Alec, we’ve won,” his father said.

More than 200 people were arrested that day. Facing trespass charges, they were bundled into the back of police vehicles which swung back and forth as waiata rose from inside.

They eventually arrived at the central Auckland police station and, to this day, Hawke still doesn’t know how they managed to fit everyone inside.

The first ones processed were the kaumātua, followed by the whaea, recalls Hawke. Everyone else followed behind in tranches.

“Haka rang out … there was noise … I heard that they could hear it five storeys up.”

He vividly remembers asking the police liaison officer about his mother, who was being held elsewhere in the station.

Hawke visits his daughter Joannee’s memorial at Takaparawhau often. Ricky Wilson / Stuff

It was awful, says Hawke flatly. Police had arrested his mother and, in the eyes of many, his brother Joe was now public enemy number one.

“It was more devastating for him. Just imagine the weight that he had to bear as a leader and to see that happening on his own land.”

It was also tragic in a social and historical sense. New Zealand was supposed to be free and democratic – its race relations were considered leagues ahead of other countries, says Hawke.

After being released, the protesters returned to Takaparawhau, only to find it covered in more police.

“For two weeks, all of Takaparawhau/Bastion Point was a squadron of police. And they were five yards apart, so you couldn’t get back there … there were searchlights that shone out all over Ōrākei.”

Hawke and his whānau set up camp at the marae. Occasionally people would try to head back to Takaparawhau, which resulted in more arrests.

“It was 506 days since the occupation began. It was 26 years since the families of the action group had been evicted from the papakāinga, the original marae and village destroyed and only the cemetery left,” the 1987 Ōrākei Claim Waitangi Tribunal report read.

Regrouping and rebuilding

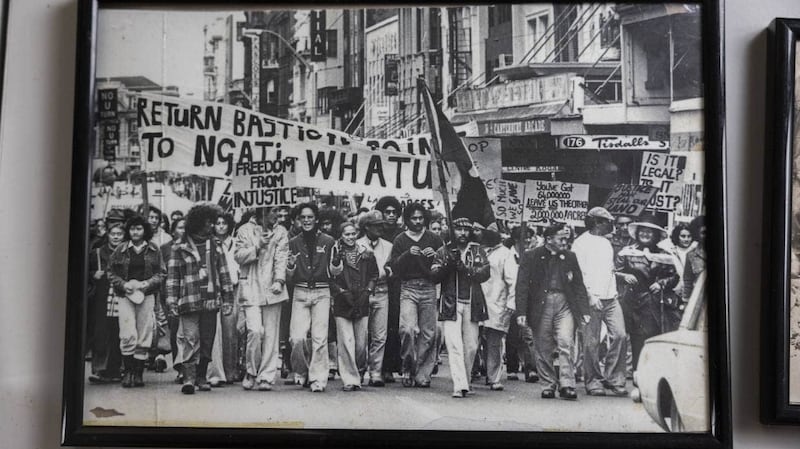

The next big battle would focus on getting everyone’s charges dropped. Hawke recalls countless marches at that time, which he says typified the Boot Hill spirit.

According to the Ōrākei Waitangi Tribunal report, some protesters would later plead guilty, be convicted, and then be discharged.

Others pleaded not guilty and instead elected to be individually tried. This resulted in the attorney-general at the time, Keith Holyoake, electing to stay the remaining prosecutions, the report said.

More than 20 of those convicted appealed to the High Court but were unsuccessful. Some decided to take their fight to the Court of Appeal, where their convictions were quashed.

The Boot Hill kids marched down Auckland’s Queen St in a bid to get their charges dropped. Ricky Wilson / Stuff

It wasn’t all political action though. The Boot Hill kids also had to set about rebuilding their lives, including Hawke.

A lot of the protesters struggled to find work following the occupation and several were forced to rely on social welfare, says Hawke.

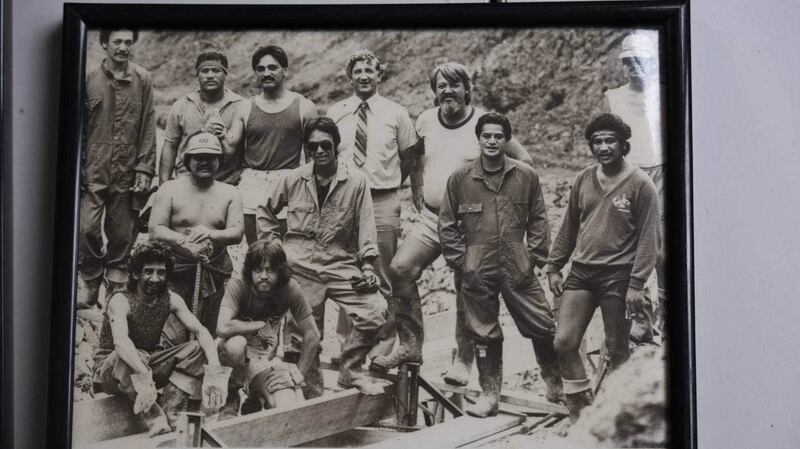

Facing the prospect of long-term unemployment, he and others formed a work trust where they would bid for labour-intensive contracts.

Then there was the emotional rebuild. Ngāti Whātua had been through a traumatic experience and relationships had been tested.

Multiple sports clubs were set up for netball, rugby league and touch rugby, says Hawke.

“We were at the forefront of the waka ama coming to New Zealand … we were one of four clubs that set up a national body.”

The Boot Hill kids started a work trust as people struggled to find employment after the occupation. Ricky Wilson / Stuff

“We bid for the world sprints in 1990, and we got it. We hosted it down at the Ōrākei Basin along with the Commonwealth Games.”

A waka was built, and support was offered to all the boards who were leading Treaty negotiations at the marae.

“It was a joyous occasion when we got the land, the title of our land back at Bastion Point … we celebrated that like it was a victory.”

Joe Hawke would go on to enter Parliament in 1996 with Labour. His commitment to the whenua never faltered, uttering the phrase “give our land back” twice during his valedictory speech.

Several more Ngāti Whātua occupations followed, notably inside Auckland Railway Station where the iwi planted its large waka, says Hawke.

“So we had a lot of victories along the way. And temper that with sadness … a hard road, but I think our ancestors would be proud.”