Elephants have long been a part of the cultures and traditions of Asian countries, but animal and man are now competing for land. Video journalist Rituraj Sapkota visits a village on the border of Nepal and India that’s seeking creative solutions to its elephant problems.

Shankar Chettri Luitel is the go-to guy for all things relating to elephants.

“I am not a scientist and I do not have qualifications,” he claims as he introduces himself. But for more than a decade he has been photographing the elephants that walk into his village from across the Mechi River, which forms the boundary between India and Nepal.

Luitel’s village, Bahundangi, is in the Jhapa district of Nepal and sits on the western bank of the river. Every year during harvest season, herds of elephants numbering anywhere from a dozen to over a hundred cross the border from West Bengal in India into Bahundangi and help themselves to the corn and rice.

Older, solitary males that live in the forests on the Indian side, also pay regular visits.

But every time brings conflict.

“It has been like this since I can remember,” says Luitel (50). Villagers come out in large numbers and do everything they can to chase the elephants away, shining flashlights in their eyes, banging tin sheets, honking motorcycle horns and letting off firecrackers.

Shankar Chettri Luitel has been photographing and documenting elephants for over a decade. Photo / supplied

“Generations have grown up watching out for elephants and chasing them,” he says.

Arjun Karki, who chairs the Mechinagar Ward 4 within the district gives a more detailed background.

“Our fathers and grandfathers came here (from the hills) in 1949. They ploughed fields and grew rice but didn’t initially come in contact with elephants. Now we know the elephants were always there but they had plenty to eat in the forest and did not enter villages.”

In the decades that followed, that all changed as the population grew and the village expanded. Man and animal began to cross paths and in 1978, a woman was killed by an elephant.

“It was then that people realised that this animal could kill humans,” Karki says.

Some people pulled out spears and knives, others lit incense sticks and blew conches to appease the elephant god. But elephants came to be regarded as a pest and the government provided guns for villagers.

“For the next 50 years, we killed it and it killed us. But it hasn’t disappeared and neither have we,” he says.

Photos of elephants (mostly taken by Shankar Luitel) hang on the walls of Arjun Karki’s ward office, as well as an elephant figurine he commissioned a local artist to make.

“We are dealing with two intelligent species here,” Dr Sanjeeta Pokharel says.

She’s a biologist who studies elephants including the relationship between man and beast in different parts of the subcontinent, and the stress physiology of elephants in conflict zones and in the wild.

“I don’t like to use the word conflict,” she says. “I prefer to call it negative interaction. There are positive interactions too.”

One thing is common in most places, Pokharel says.“People and communities on the frontlines are very poor. Their harvest is all they have got.”

But the elephant is supremely unaware of ownership and international borders and it only sees habitat, Pokharel says. They’re also highly locomotive, which leads to continuous migration.

The elephants also panic easily and when they come face to face with hostile crowds or individuals, unfortunate incidents happen.

Dr Sanjeeta Pokharel works with Kyoto University in Japan and has been researching the elephant perspective in adverse human-elephant interactions.

Since 1973, 55 people have been killed by elephants, and 55 elephants have been exterminated in the Nepali district of Jhapa. Photo: Shankar Chettri Luitel

Luitel believes co-existence is futile unless people have alternative means of income or a guaranteed livelihood.

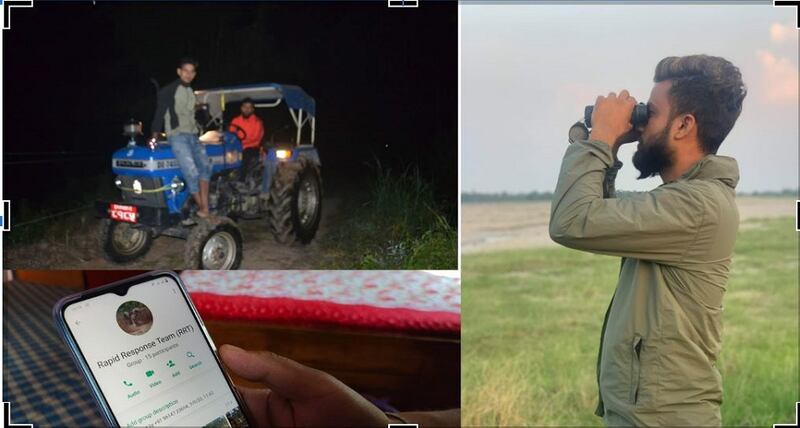

Luitel has introduced me to Newton Karki, a member of a newly formed rapid response team.

“I grew up chasing elephants,” Karki says. “Nobody from outside can solve this for us, it’s something we must do ourselves. Hence, this team.”

Karki says the rapid response team ensures both elephants and humans are safe.

The rapid response team springs into action when elephants crossing the Mechi river are sighted. It’s made up of local men who rely on their lived experience and interaction with elephants to predict their behaviour.

They’ll try to divert the elephant (or herd) towards open fields or back to the Indian side and, if they enter a village, try to chase them to an area where they will cause minimum harm.

“They might damage some crops that way but we want to make sure nobody dies,” Karki says.

Pokharel says long-term solutions can be tricky.

“If there are 200 families and one elephant, you can remove the elephant. If there are 20 families and a thousand elephants, you could move the human settlement.” Both are scenarios she has seen elsewhere in the subcontinent.

But the village of Bahundangi is neither. It’s a large settlement in a very long elephant ‘corridor’.

“We can’t stop elephants,” Newton says. “We have dug trenches and built fences, we have rubbed chilli on the fence wires. Electric fences worked for a bit. But it finds its way around every new idea we come up with.”

But Karki sees no alternative to co-existence.

“The elephant must eat, too,” he says.

An elephant deftly maneuvres past a live electric fence. Its behaviour has evolved to overcome most deterrents and barriers.

Arjun Karki talks passionately about the idea of making an abundance of food for elephants. The plan is to convert an area – some of it no man’s land – between the outer edge of the village and the river banks into plantations where elephants can feed so they don’t have to enter villages.

“Instead of going out with pitchforks and crackers when they hear elephants, they’ll turn their backs and go to sleep,” he says. “No one gets hurt.”

Eco-tourism is an off-shoot of this plan, where people can observe elephants feeding in these demarcated zones and open shops and home-stays for visitors. Instead of elephants being an adversary, they become an opportunity.

The idea seems to be catching on. Karki has been invited to India to share Bahundangi’s experience to response team volunteers and localyl elected representatives from both sides of the border, forest officers, wildlife researchers, and members of India’s border police force who man the open border.

A watch tower on the banks of the Mechi River where India’s border police are usually the first to spot elephants crossing over.

Luitel was also at the meeting and pleased with its outcome.

“I wish we had agreed on them 15 years ago.”

Rituraj Sapkota is a Te Ao Māori News video journalist who is travelling in South Asia and writing about conservation, sustainability and indigenous communities.