Photo / File

By Benn Bathgate, Stuff

It’s the “usual stuff” that has created the Māori housing crisis, according to economist Shamubeel Eaqub.

“Colonisation, dispossession, racism.”

Eaqub was among the speakers at the biennial Māori Housing Conference in Rotorua, where more than 900 attendees gathered to hear government ministers, iwi housing providers and a host of other stakeholders speak over three days.

The event’s aim, according to co-chair of the organising committee Lauren James, is to “change the narrative” on Māori housing.

“Our intention organising this wānanga was to canvas the housing continuum as broadly and deeply as possible – to achieve a balance of focus that covers papakāinga solutions, affordable rental and homeownership, homelessness, climate change, economics, Treaty and human rights, construction, and innovation through to what our next-gen rangatahi are saying about housing security in fresh research.”

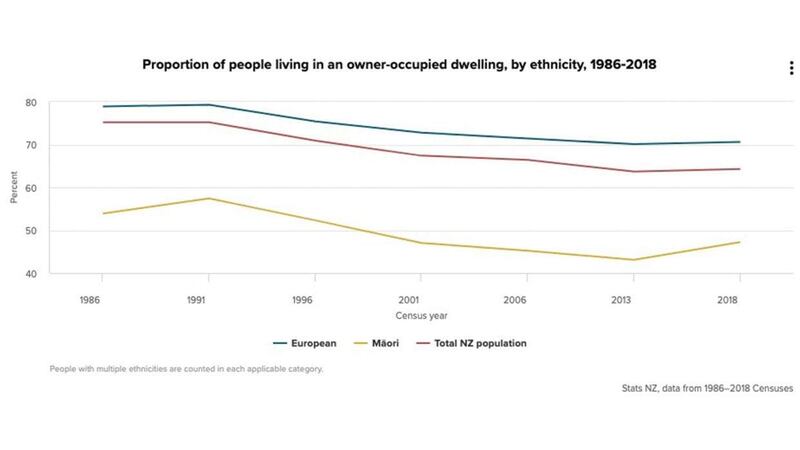

Some of the stark issues facing Māori in the housing space are clearly laid out in Census 2018 data.

Māori are more likely to live in homes affected by dampness or mould than people with European ethnicity, with two in five Māori living in damp housing compared to one in five people of European descent.

Around one in five Māori live in a crowded home compared to one in nine of the total population.

Exactly how the Government should respond was spelled out to attendees by Associate Housing Minister Marama Davidson.

In short, it needs to “decolonise the power and resources out, devolve the bureaucracy and get out of the way”, Davidson said.

Associate Housing Minister Marama Davidson told the conference the best thing Government can do to help address the Māori housing crisis is simply “get out of the way”. Photo / File

She also cited the iwi-led Covid-19 response work as a model that could be used in the housing space, where an effective response mechanism was identified and “more trust had to be given over to our communities”.

Her stance was echoed by both Housing Minister Megan Woods and Minister of Māori Development Willie Jackson.

“We have been made houseless and decolonisation and re-indigenisation will pull us through that,” Davidson said.

According to conference co-organiser and general manager of the Te Matapihi body for Māori housing providers, Wayne Knox, that’s the key response they want from the Government.

He opened the conference with the blunt message: “Give us the resources and get out of the way.”

He said he believed the Government was walking the walk too.

“We’re seeing some examples of how that’s happening, and it’s working,” he said.

“Iwi putting forward their models.”

The shared equity model of Ka Uruora, a collective between Taranaki and Te Ātiawa iwi, was one such example.

2018 Census data showing the proportion of people living in owner-occupied dwellings, by ethnicity, between 1986 and 2018. Source / Stats NZ

Ka Uruora delivers financial stability and independence to whānau through education, WhānauSaver – an exclusive invested savings fund with iwi contributions - and multiple homeownership models.

Under the housing programme, Ka Uruora will share the purchase cost and ownership of housing offered until whānau can afford to take full ownership.

Ka Uruora chair Jamie Tuuta told the conference its model was essentially whānau then whare.

He said the organisation started with financial education courses with the whānau it work with, reasoning that “if we could build the financial capability and understanding, our whānau would have better choices”.

“To create a really great foundation for better decision-making.”

Ka Uruora chair Jamie Tuuta. Photo / File

Tuuta said they had been happy to share their model and ways of working with iwi across Aotearoa too, something Knox said was one of the successes of the conference.

“We see examples like that constantly. They’re happy to share their models, what works.”

Knox said that between the first conference in 2010 and now, what had changed was “only everything”.

He cited a number of issues such as inflation pressures, rising interest rates, a cost of living crisis, natural disasters and new restrictions of borrowing.

There were items on the plus side of the ledger too, however.

The “sea change” establishment in 2018 of the associate minister of housing (Māori Housing) role, the establishment of the Māori Housing Unit within the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development and the Budget 2021 investment of $380m in Māori housing.

Wayne Knox, general manager of Te Matapihi, said there had been a realisation that iwi simply needed to get on with the job themselves. Photo / Sarah Sparks

Speaking as the conference drew to a close on Friday, Knox said he was optimistic about the progress made, and future progress, but he wasn’t without reservations.

“There’s always concern around election time,” he said.

“Labour have been great, they have listened and made some bold moves... Though in some areas they haven’t been as bold as they needed to.”

Ultimately though, he said a collective point had been reached where iwi knew they had to implement their own solutions, with or without government assistance.

A stark warning about reliance on Crown funding, or “lolly money” was also issued by human rights lawyer Annette Sykes in the conference’s most combative address.

Sykes said she wanted to begin her korero with a minute’s silence for two child deaths that took place in Rotorua’s emergency housing among “people isolated from their whānau”.

Sykes didn’t pull any punches when she took aim at “the racism in the underbelly of this town, which is also led by Māori”.

“People like [homeless charity founder] Tiny Deane were literally dealt with by our own iwi as an outsider... Someone taking money off the misery of our people,” she said.

“A mean-spirited response, led by many Māori leaders in this room. Did you lead or did you just put the boot in?”

Annette Sykes (centre) pictured with Donna Huata and Justice Minister Kiritapu Allan on Waitangi Day. She warned iwi to be careful of depending on Crown cash to solve Māori housing issues. Abigail Dougherty / Stuff

She said if in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, and beyond, “outsiders” had sought accommodation in Rotorua it was for a simple reason – their ancestral land had been taken from them.

She also took aim at housing providers in the audience, saying some had simply adopted a neoliberal economic model that did nothing for the poorest Māori in the community; people she said earned as little as $17,000 a year.

Sykes also put a direct challenge to the members of the richer iwi in the room: “are you ready to invest in houses for our people?”

“You don’t need a government policy to do that, you need a conscience.”